Build Effective Social and Behavior Change Strategies

By Judd Devermont

Former senior advisor to Fraym

In 2017, UNDP publishes ground-breaking report entitled “Journey to Extremism in Africa: Drivers, Incentives, and the Tipping Point for Recruitment.” The study was drawn from an unprecedented number of recruits from multiple violent extremist groups spanning the continent. Two of its most important findings were:

• Economic factors are key drivers of recruitment. Individuals who joined violent extremist groups cited poor economic conditions, including poverty, unemployment and underemployment, as a “major source of frustration.” If an individual was studying or working, UNDP judged that she or he would be less likely to join an extremist group.

• The experience of suffering abuse at the hands of government is a “tipping” point for joining extremist groups. Seventy-one percent of individuals surveyed in the study pointed to the “killing of a family member or friend” or “arrest of a family member or friend” as the incident that prompted them to join.

I wanted to explore whether Fraym’s human geography, combined with geolocated government operations, could identify towns and villages in northeast Nigeria with greater susceptibility to Boko Haram or ISIS-West Africa (ISIS-WA) recruitment.

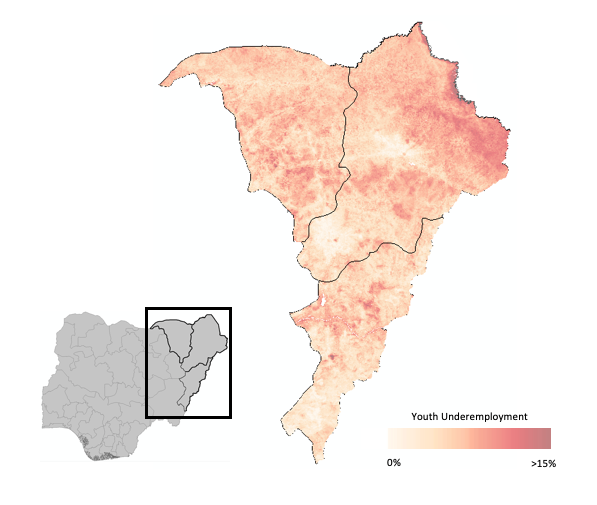

First, I used Fraym’s human-centric data-layers to identify areas where there is a higher proportion of underemployed youth. The map below indicates that there is a higher proportion of vulnerable youth on Borno state’s eastern border with Chad and Cameroon Notably, this area is near the Lake Chad Basin, where ISIS-WA operates, and relatively far from major highways.

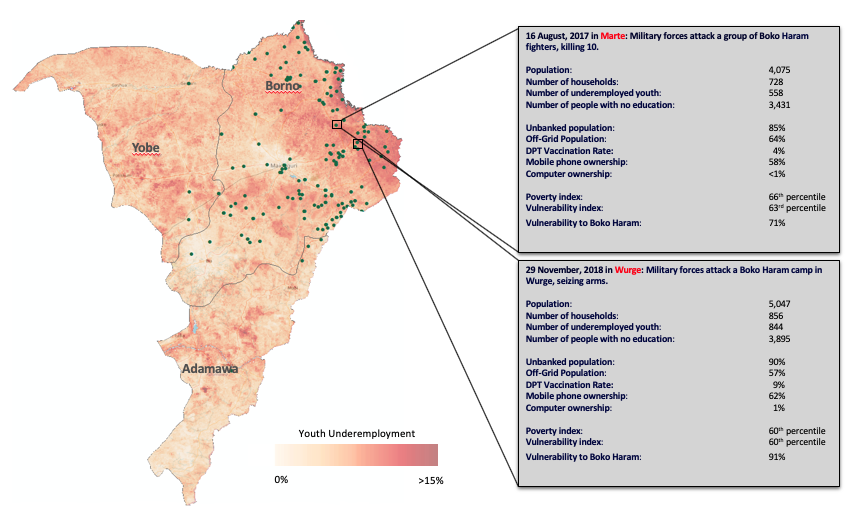

Next, I geolocated government-initiated operations against Boko Haram or ISIS-WA between 2017 and 2019.These towns or villages are more likely to have experienced abuse by the security services. By leveraging Fraym’s human-centric data-layers, I was able to develop a profile of specific locations, such as the towns of Marte and Wurge, where UNDP’s findings of high underemployment and potential government abuse appear most relevant.

In addition to having experienced government-initiated operations, both communities are vulnerable to Boko Haram attacks. Fraym’s machine-learning algorithms identify both Marte and Wurge as reflecting the socio-economic, demographic, and geographic characteristics of communities that Boko Haram has a pattern of attacking. On a scale of 0 to 100 (highest), Marte and Wurge respectively score 71 and 91.

In conclusion, Fraym’s unique data sources enabled me to apply findings from the UNDP’s “Journey to Extremism in Africa” report to northeast Nigeria, identifying specific towns and villages in northeast Nigeria with greater susceptibility to Boko Haram or ISIS-West Africa (ISIS-WA) recruitment. These results could help the Nigerian government and its international partners direct new programs and initiatives to these areas, as well as refine Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE) interventions.