Build Effective Social and Behavior Change Strategies

By Judd Devermont

Former senior Advisor to Fraym

Since October 2017, a violent insurgent group—invariably called al-Shabaab or Ahlu Sunna wa Jama (ASWJ)—has conducted some 139 attacks, with more than 350 civilian and military deaths. There is not a consensus about the group’s identity, objectives, recruitment, or funding sources. Moreover, there is a hotly contested debate about linkages between local, regional, and international extremist networks.

Some scholars, in contrast to those promoting an international terrorist nexus, have noted that ethnic tensions in this region of northern Mozambique are a contributing factor to the conflict. Eric Morier-Genoud, for example, suggests that the Mweni, which reside on the coast and are one of the main ethnic groups in the region, have been recruits for ASWJ. He explains that the Mweni have felt “marginalized for decades by migration into their area, a lack of economic development, and their neighbors’ political clout.” These other neighbors include the Makua, which are the largest ethnic group and live in the mountainous interior, and the Makonde, who live along the border with Tanzania and claim President Nyusi as a native son.

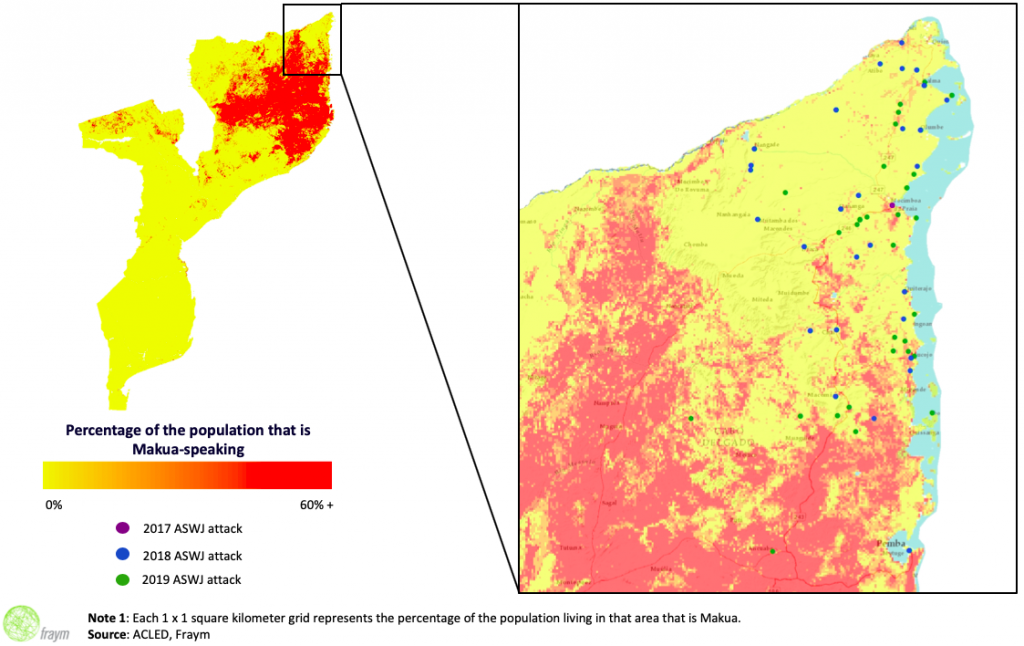

Through Fraym’s human geography data, we wanted to examine the ethnic dimension to the conflict. Specifically, does ASWJ operate primarily in Mweni territory?

By combining a base layer map depicting the percentage of Makua language speakers—which is the only one of the three languages available in survey data–with attack locations, we discovered that most of the attacks (93 percent) have been conducted in areas with a low-density of Makua speakers. This finding affirms explanations that stress the insurgency’s local roots, especially its ethnic component.

The correlation between attack locations and low-density Makua speaking regions raised a second question: how does Fraym data account for the cluster of attacks in Cabo Delgado’s Makua areas in the interior and Makonde communities on the northcentral border with Tanzania?

To address this paradox, we used time-lapsed animation to track the group’s attacks from 2017 to mid-2019. This resulted in two insights. In 2018, ASWJ indeed conducted several probing attacks into Makua and Makonde territories.

However, it appears that ASWJ in 2019 switched its tactics, refocusing on its operations on the coast and road networks instead of continuing to expand its footprint into Cabo Delgado’s interior.

This shift in its operations could indicate that ASWJ had failed to recruit a sufficient number of fighters in non-Mweni areas and struggled to operate in less familiar terrain in the center and northcentral border region.

In conclusion, Fraym’s unique data enabled us to test some of the competing explanations for the conflict in northern Mozambique. We concluded that ethnicity is an important factor—perhaps more so than previously assessed—in the insurgency. Fraym’s pairing of ethnic, religious, and topographic layers with attack data raises questions about ASWJ’s support base and its capacity to expand out of its strongholds along the predominately ethnic Mweni coastline.