Build Effective Social and Behavior Change Strategies

By Judd Devermont

Senior Fraym Advisor

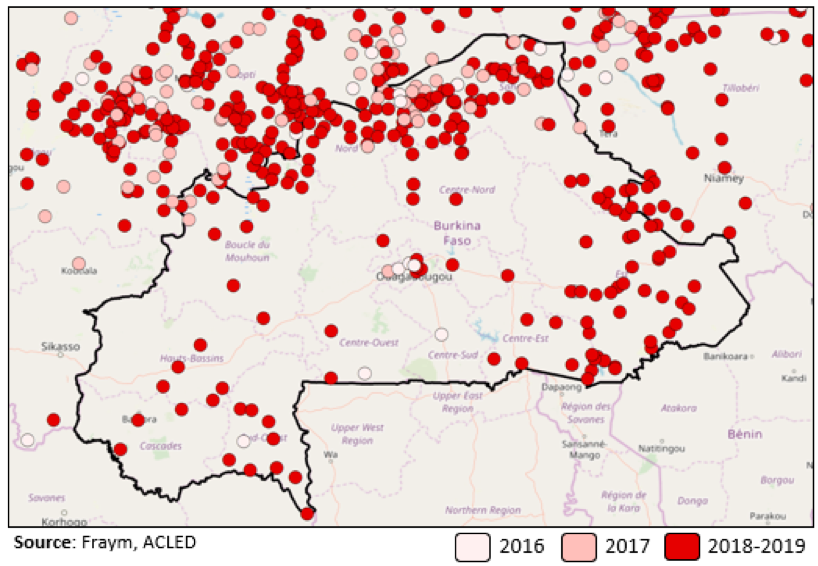

Since 2016, the country has suffered three high-profile attacks in its capital Ouagadougou and experienced persistent outbreaks of violence, including kidnapping of expatriates, in its northern and eastern regions. In February, Burkinabe Foreign Minister Barry warned that “The threat is gaining ground,” and it could spread to coastal West Africa. Burkina Faso’s insecurity has alarmed its regional and international partners, spurring the U.S. military to consider sending additional military advisers as well as intelligence and surveillance assets such as drones to Burkina Faso. I wanted to test whether Fraym’s human geography data could help us identify potential factors underlying the country’s susceptibility to extremist violence.

First, I geolocated all of the terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso between 2016 and early 2019. The data shows that Malian insecurity expanded first into Burkina Faso’s northern regions and then spread primarily to its eastern regions.

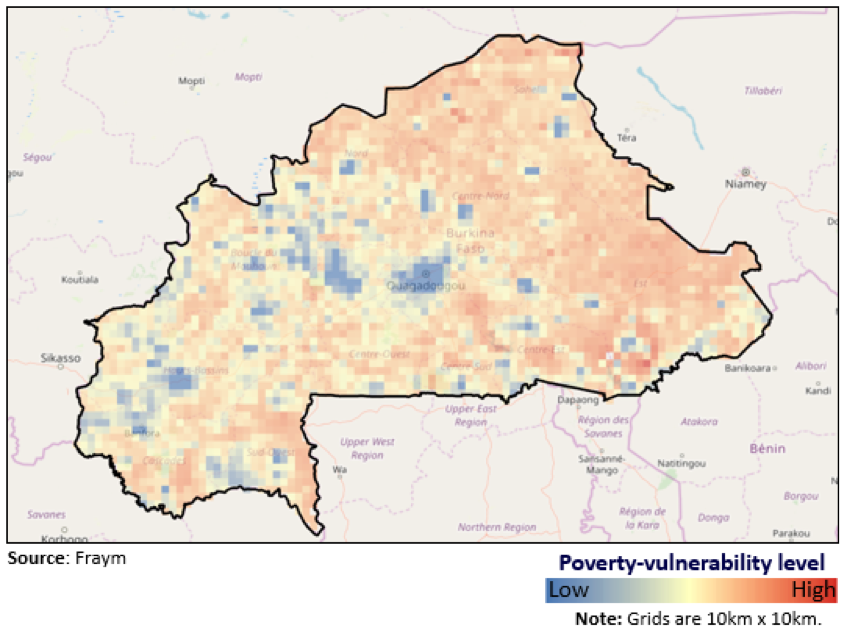

Second, I used Fraym’s vulnerability and poverty indices to identify where Burkina Faso’s most vulnerable communities reside. As part of the Fraym vulnerability index, we consider unemployment rates, access to infrastructure, literary rates, and societal norms around violence towards women. The data shows that many of Burkina Faso’s most vulnerable communities reside in regions experiencing high levels of extremist violence.

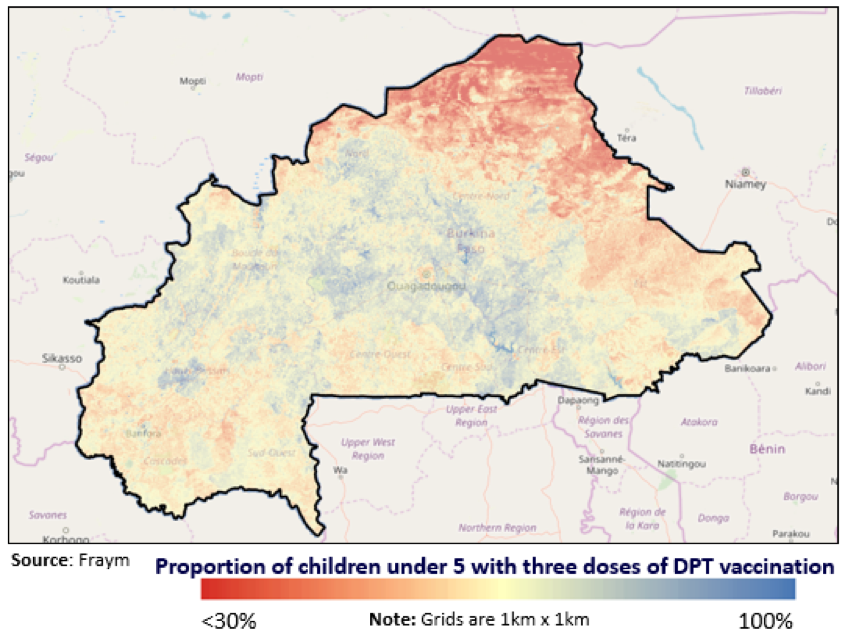

Third, I employed Fraym’s vaccinations data as a rough proxy for state capacity to uncover whether Burkina Faso’s government has regular access to the most affected areas. The data shows that the Burkinabe government has been least successful in vaccinating its under-5 populations in the northern and eastern regions, suggesting its access to these regions is comparatively limited.

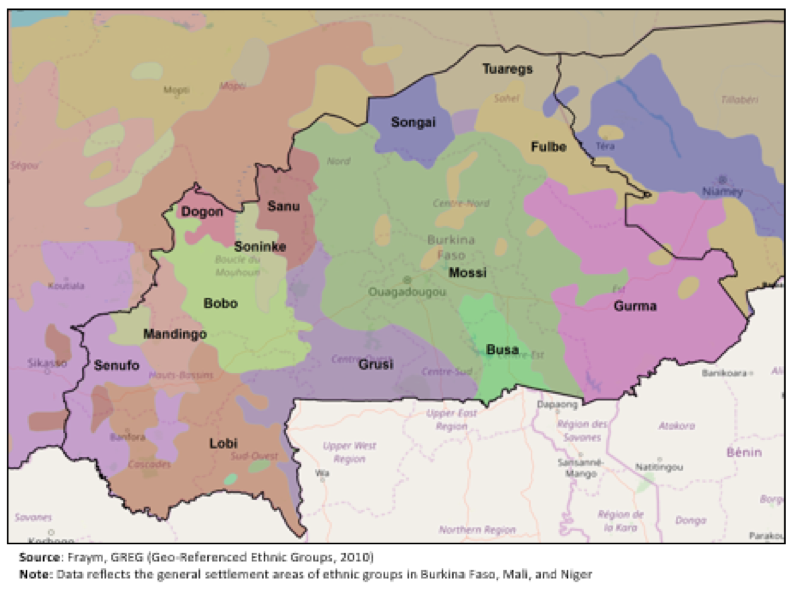

Finally, I examined Burkina Faso’s ethnic composition. Most experts agree that regional and local extremist groups, including Jama‘at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), Ansaroul Islam, and ISIS-Greater Sahara, have been exploiting ethnic Peuhl (also known as Fulani) disaffection and tensions between Peuhl and Tuareg communities to sow violence and unrest. Fraym’s access to ethnic maps indicates some overlap between the locations of attacks and Peuhl and Fulani areas. However, I found this to be the weakest factor because of the limitations of ethnographic mapping and the partial match of attacks and ethnic zones.

In conclusion, Fraym’s unique data sources enabled me to develop an analytic framework to understand extremist trends in Burkina Faso. I determined that three and possibly four factors increase a Burkinabe region or community’s susceptibility to extremist violence: proximity to Mali, community vulnerability, government reach, and possibly ethnicity. I intend to use this framework—paired with qualitative reports on governance, local grievances, and security sector abuses—to track, measure, and explain what is happening in Burkina Faso.