Build Effective Social and Behavior Change Strategies

As the pandemic continues to unfold, already struggling regions are now grappling with the next effect of COVID-19: the wholesale crippling of global and domestic food supply chains. Children under five are particularly at-risk and often suffer the most in countries vulnerable to famine or that are highly dependent on food imports.

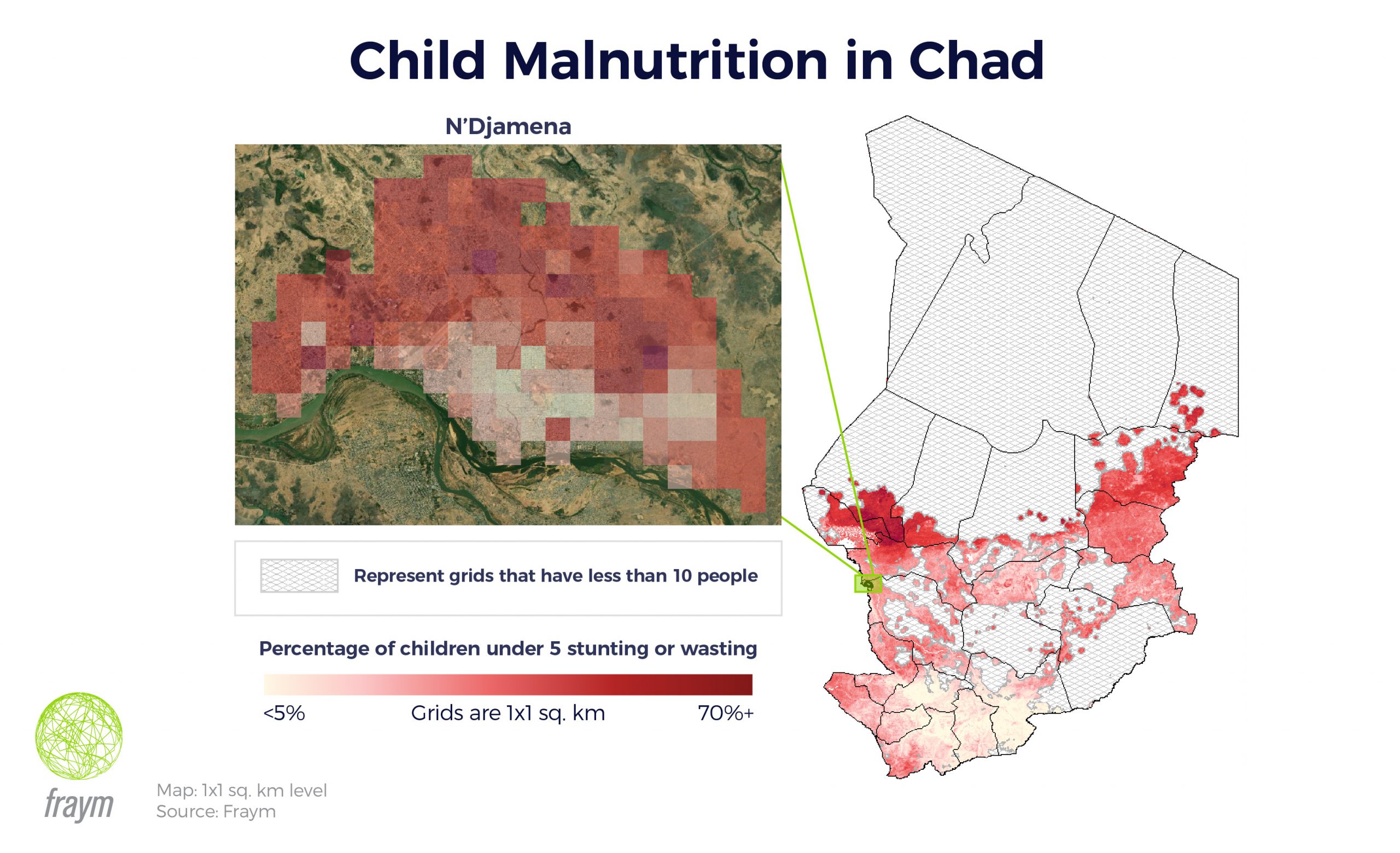

Fraym used its machine-learning based approach to identify areas with high rates of under-5 stunting and wasting in Chad, a country that is also struggling with collapsed oil prices and pre-existing food security challenges. This approach identifies potentially vulnerable communities throughout the country with a high level of detail–and illustrates the particularly dire situation in the capital city of N’Djamena. Food insecurity in large urban areas, something rarely seen in the recent past, will have explosive social and political consequences for Chad and countries across the global south. Our goal is to use local spatial data to help policymakers anticipate and mitigate these consequences.

N’Djamena has relied on food imports from abroad for many years. This, coupled with being nearly 1,900 kilometers from the nearest deep water port, has contributed to one of the highest costs of living on the continent – even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, more than two out of every five children suffer from stunting or wasting. By comparison, that rate is almost twice as high as rates in Lagos and Bamako, which are 19 percent and 23 percent respectively. In addition, baby formula, the alternative to breastfeeding, is heavily dependent on import systems functioning properly. In a shock, such as this pandemic, thousands of children may be at risk of not receiving critical nutrients at an early age. Breastfeeding amongst adult women in N’Djamena is low compared to the rest of the country, only 22 percent of women breastfeed, which is 12 percentage points lower than the national average. This may reflect the capital’s higher usage of baby formula as well as smaller families, and helps quantify the risk that mothers and their children face with food shortages that may occur in the city.

These numbers are likely to rise, with high percentages of the population in job markets that have shrunk under COVID-19 restrictions, like manual laborers and food stall and restaurant workers. Within areas with high food insecurity risks, Fraym data further maps populations in occupations who may be among the first impacted by rising food prices and reduced incomes. For example, livelihoods in N’Djamena were dramatically altered when the government quarantined the city on May 10, despite large numbers of workers who had already left in search of work. According to Fraym data, nearly half of the city’s workforce rely on market-oriented occupations, such as small shop owners and artisans. With higher prices and weaker job opportunities, children in these households will face worsening nutrition outcomes. With this information and Fraym’s granular mapping, governments and implementers can target efforts like infant formula kits or cash transfers at the neighborhood level to allow parents in need to provide for their children.

Large cities across the Global South are facing similar challenges to N’Djamena. But with hyperlocal data on the populations who may be most affected, their existing challenges, and where to reach them, policymakers and implementers can employ data-led strategies to prevent child hunger and mitigate resulting instability.