Build Effective Social and Behavior Change Strategies

As the world focuses on the fight against COVID-19, extremist activity has increased in some places. On March 23, the deadliest Boko Haram attack in Chad’s history occurred, with militants killing at least 92 troops. To help us understand how Boko Haram selects their targets, we analyzed the economic standing of villages that have been attacked.

Boko Haram has been active since 2002, surviving government military campaigns and enduring a factional split in 2016. Boko Haram’s resilience, in contrast to the Islamic State faction, is often ascribed in part to its practice of raiding unprotected villages to obtain supplies. Many experts believe Boko Haram funds itself through kidnap for ransom, taxation, and pillaging local communities. The Combating Terrorism Centre at West Point, the US military academy, noted in a 2018 report that Boko Haram employ a ‘live-off-the-land’ approach, “stealing food, medicine, and other supplies during operations, including hijacking trucks and cattle-rustling.” Using advanced machine learning (ML) models to produce local-level population data, we wanted to test this theory. If Boko Haram is subsisting by robbing local communities, we would expect the extremist group to more consistently target high-value areas in its attacks.

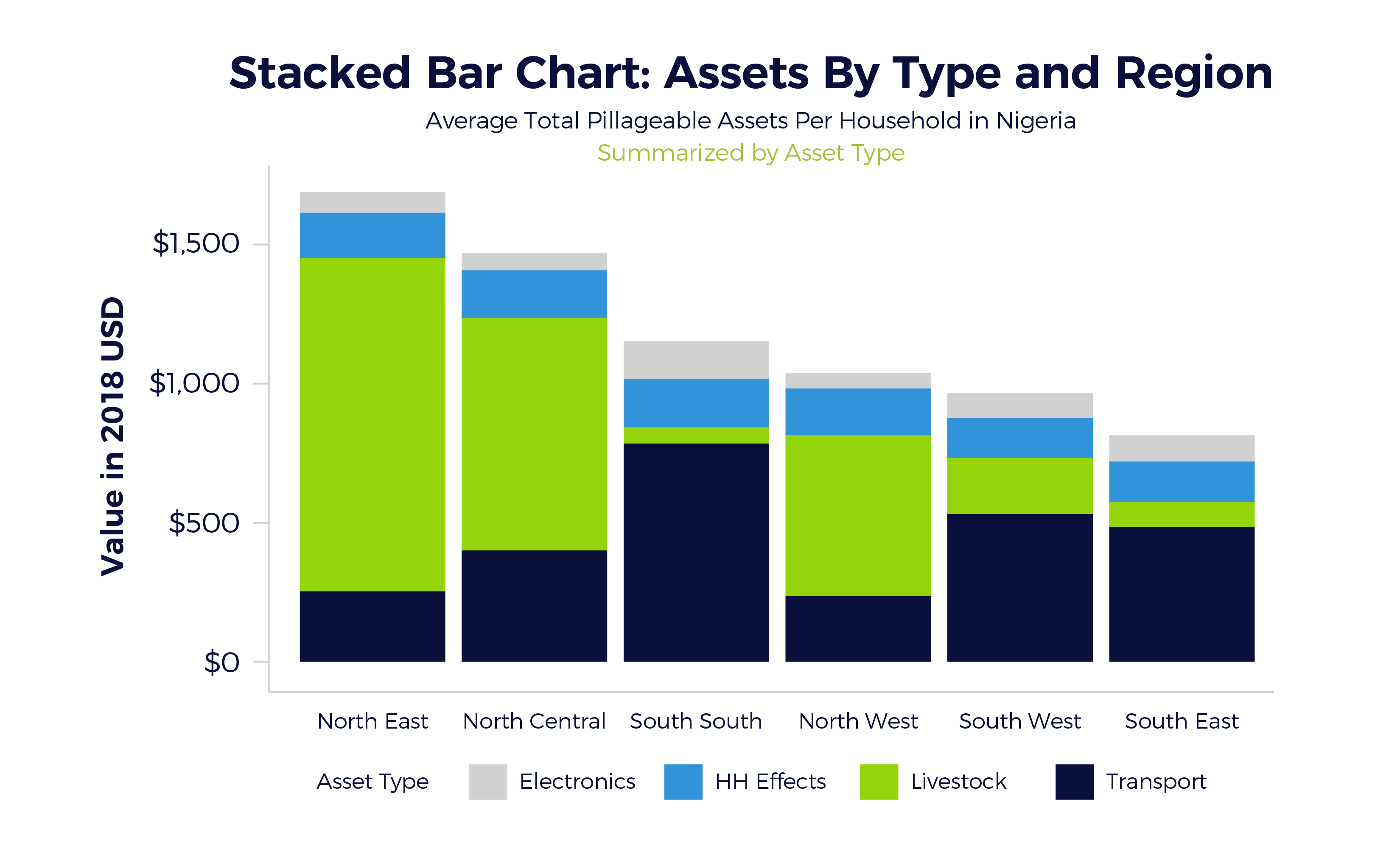

Using Fraym’s cutting-edge data, we developed a methodology to measure the value of pillageable assets—electronics, livestock, household effects, and transport vehicles—in cities and rural communities across Nigeria. We measured the value of each pillageable asset in a household based on the household’s perceived value of the asset if it were to be sold. The values of each asset were then summed to create a ‘total pillage value’ for each of these households. We found that northeast Nigeria, where Boko Haram operates, is richer in pillageable assets than the rest of the country. The disproportionate number of livestock, such as cattle, goats, and chickens, in northeastern states such as Taraba and Borno, was central to this finding.

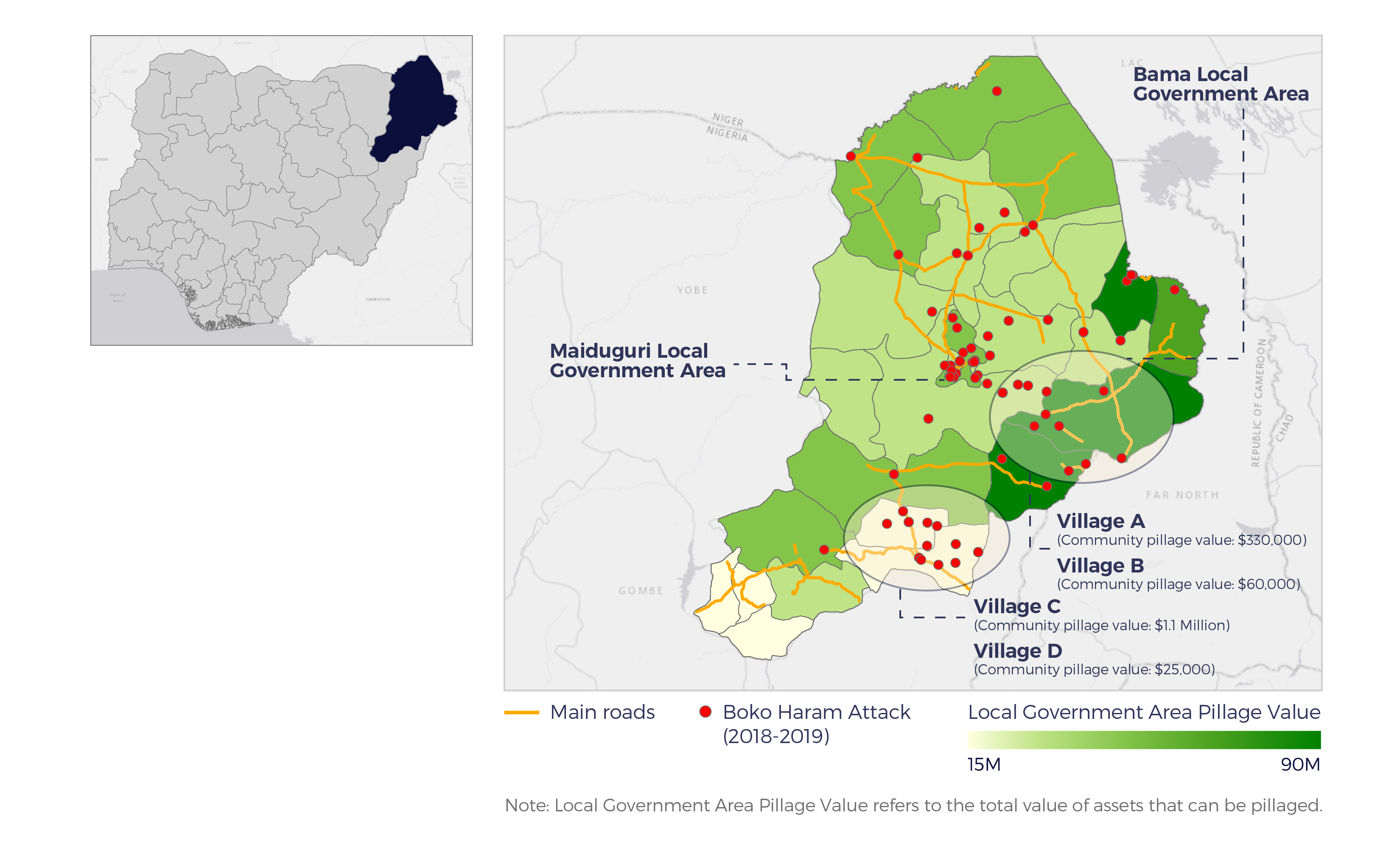

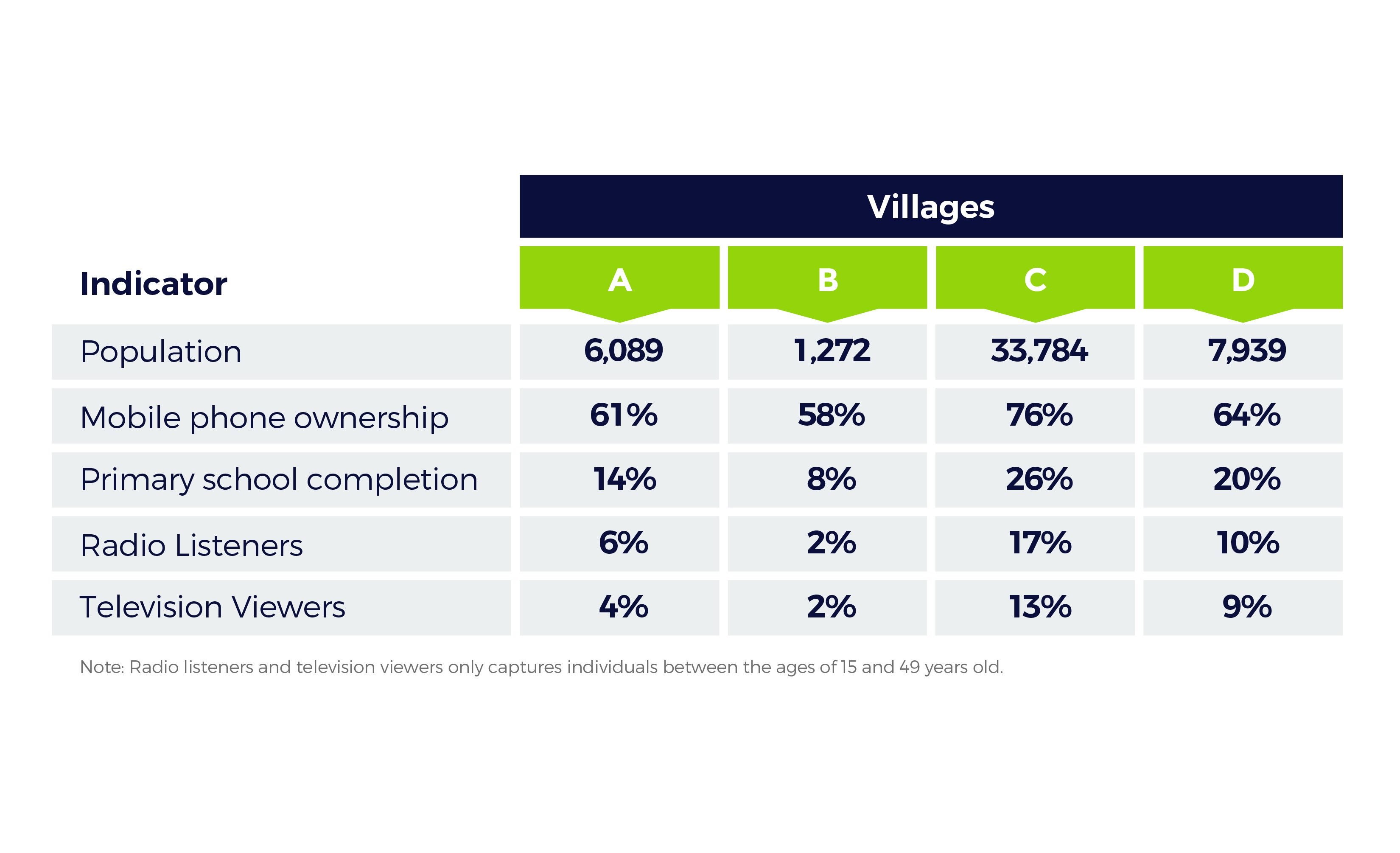

We looked at two pairs of towns connected by at least one road, within 30 km of each other, and located in Boko Haram’s zone of operations. In both cases, Boko Haram attacked a low-value town with at least one attack. Despite the proximity, the group neglected to target the higher-value community. There were probably several reasons for the group’s target selection—perceived collaboration with the government, receptivity to Boko Haram’s ideology, fissures within the community—but an imperative to loot and extract resources appears less significant.

In conclusion, Fraym’s ML powered economic data enabled me to visualize the financial resources belonging to communities in the war-ravaged northern Nigeria. By conceptualizing wealth as “pillageable assets”—items that Boko Haram can remove in a raid—we can render new analytic judgments about how it operates and finances itself over time. From this first review of our data, we have three principal findings:

1. Boko Haram recently has not been selecting its targets exclusively based on perceptions of a community’s wealth or pillageable assets. It may be a factor, but Boko Haram’s pattern of attacks indicates it is not decisive.

2. Boko Haram is not optimizing its attacks to pillage resources, which suggests that other revenue streams (taxation and kidnapping for ransom) may play a more significant role currently.

3. If the Boko Haram insurgency shifts its tactics, it will have access to additional resources to recruit and retain fighters, sustain government attacks, and remain a destructive and destabilizing force in the region. However, the Nigerian government and its partners will also know where to strategically position protective and responsive assets to counter this threat vector.

Boko Haram is not the only insurgent group to take a ‘live-off-the-land’ approach. Insurgent groups around the world employ the same tactics to maintain their operations. Applying newly available, granular data, we can now visualize wealth on the ground and ascertain how much value is in one community versus another. This information can be applied to any battlefield to assess the insurgency and to get a sense for their potential viability in a particular geography.