Transforming Communities, Improving Health: Rethinking Sexual and Reproductive Health for Young People

Blog

Despite the availability of HPV vaccines in Nigeria and Kenya, uptake among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) remains low. While structural barriers such as access and cost particularly affect older AGYW who are beyond the reach of national school-based vaccination programs, restrictive gender norms continue to limit vaccine knowledge, demand, and uptake across all age groups. New research from Fraym highlights how gender norms and support from religious leaders may influence vaccine knowledge, demand, and uptake among AGYW and their caregivers. By working with faith actors and promoting more equitable environments, stakeholders have a powerful opportunity to boost vaccination rates, protect girls’ and young women’s health, and greatly reduce cervical cancer risks.

This synthesis brief summarizes new research from Fraym on how gender norms, religion, and faith actors influence HPV vaccine knowledge and uptake among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) and their caregivers in Kenya and Nigeria.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a common sexually transmitted infection that can lead to cervical cancer, one of the leading causes of death among women in both countries (ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer, 2023). Despite the availability of free, safe, and effective vaccines, through national school-based programs for adolescent girls aged 9-14 launched in Kenya in 2019 and Nigeria in 2023, uptake has remained low. As of 2023, only 17% of Kenyan girls are fully vaccinated by age 15, and coverage in Nigeria for 9-14-year-olds is just 27% (World Health Organization, 2023).

While financial and access-related barriers continue to remain relevant for older AGYW (ages 15–24), who are not currently reached by national catch-up programs, restrictive gender norms affect girls and young women across all ages, 9 to 24. These norms can limit girls’ and young women’s autonomy in healthcare decisions (Alabi et al., 2024), reinforce misinformation about vaccines, reduce support for SRH education, and ultimately undermine the value placed on girls’ and young women’s health (Dutta et al., 2021; Riddle, 2024). These social and cultural barriers may help explain persistently low vaccine coverage, even where the vaccine is free to younger adolescents.

Addressing these barriers requires targeted interventions that promote gender-equitable environments, especially by promoting gender-equitable norms that affirm AGYW’s rights to information, healthcare, and informed decision-making (Riddle, 2024). Faith leaders can be powerful allies in these efforts. They hold significant influence in their communities, with recent Fraym data indicating that 88% of Kenyans and 90% of Nigerians agree that religious leaders should be respected and listened to. Past health programs have partnered with religious leaders to shift norms and increase service uptake. For example, the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) worked with Nigerian community and religious leaders to advocate for and normalize family planning services, effectively generating demand for them (“Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative – Johns Hopkins CCP,” n.d.). In Kenya, similar efforts through Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs) increased awareness and acceptance of family planning in select congregations (Bormet et al., 2021). Building on these models, this research explores how faith actors can support HPV vaccine uptake and help address gendered health barriers.

We examine three core questions:

Fraym’s analysis combines nationally representative survey data with machine-learning-powered, community-level data to examine how gender norms and faith actors influence HPV vaccine-related outcomes among AGYW in Kenya and Nigeria. In 2024, nationally representative surveys were conducted with 6,499 respondents in Kenya, including 2,296 adolescent girls and young women (AGYW, aged 15-24) and 2,089 caregivers of girls aged 8-17, and 11,356 respondents in Nigeria, including 4,646 AGYW and 3,903 caregivers. Survey data is combined with spatial data inputs (i.e., satellite imagery) to produce indicator estimates at the 1km² resolution, which are then aggregated to the third administrative level (ward) for community-level measures and analyses.

The analysis focuses on seven HPV-related behaviors and related outcomes, including vaccine knowledge, vaccination status, intention to vaccinate, and discussion of the vaccine with others. Two types of gender norms were included as independent variables. The first type focuses specifically on health-related norms. These capture perceptions among AGYW themselves and their caregivers around whether adolescent girls have access to or should have access to SRH education and healthcare without stigma (Jain, et al., 2019). These norms are considered more directly relevant to HPV vaccine uptake. The second is a community-level measure of gender-equitable norms related to decision-making, gender roles, and the division of labor. This was captured using the G-NORM scale (Sedlander et al., 2024), aggregated at the ward (ADM3) level, to provide a proxy for the normative environment in which AGYW and their caregivers live.

Multiple analytical strategies were employed to address the diverse research questions, tailored to the level of analysis (individual or community) and the nature of the indicators. Multivariate regression models were the primary analytical tool for all three research questions. These models adjusted for key sociodemographic covariates, including age, region, urban/rural residence, religious affiliation, education, and household wealth. To complement this individual-level analysis, spatial correlation methods were applied to explore community-level associations between gender norms and HPV-related outcomes at the ward level. This included calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients and analyzing the slope of the line of best fit in scatterplots to visualize and quantify these relationships.

Key Finding 1: Norms Supporting AGYW’s Access to SRH Education are Strong Predictors of Positive HPV Outcomes

Health-related gender norms—especially those endorsing adolescent girls’ access to SRH education—play an important role in shaping vaccine-related outcomes in both Nigeria and Kenya.

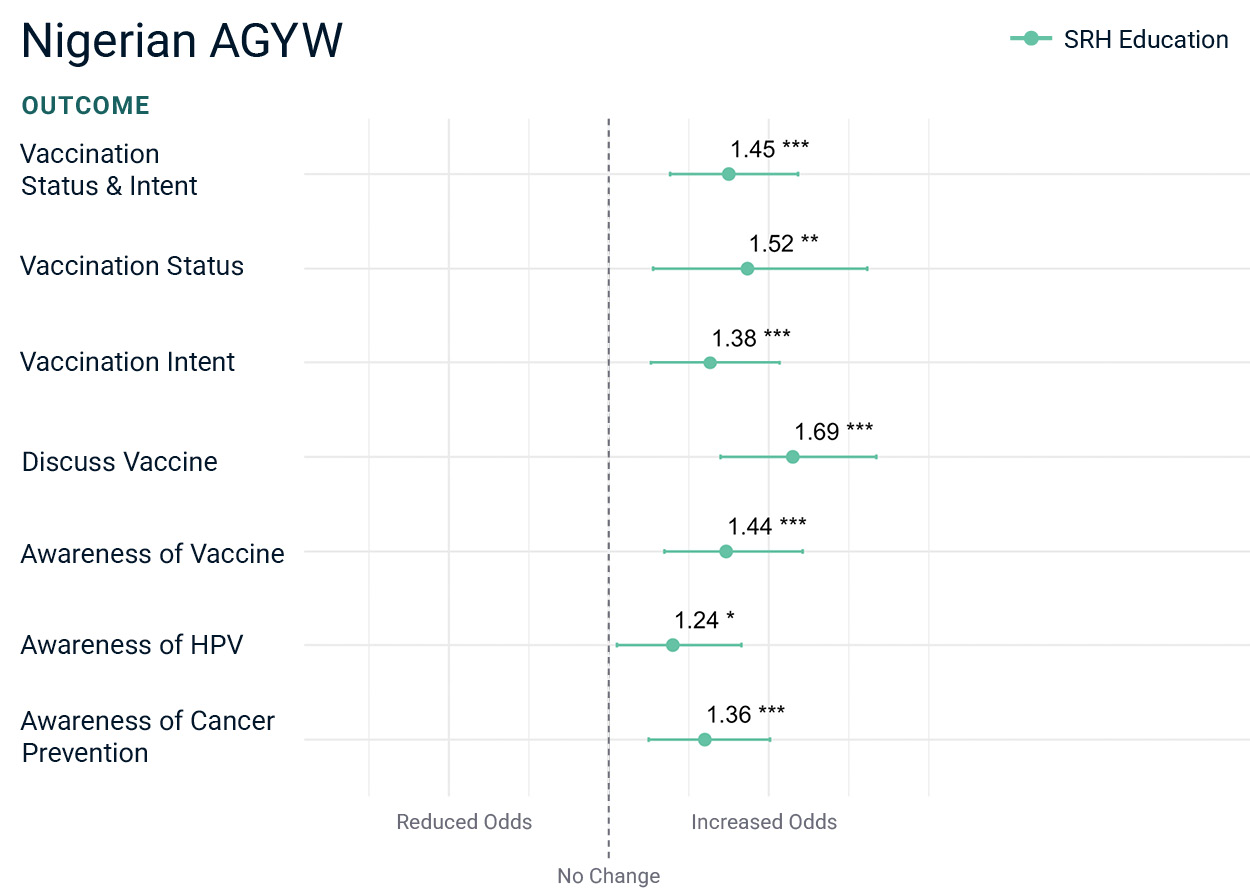

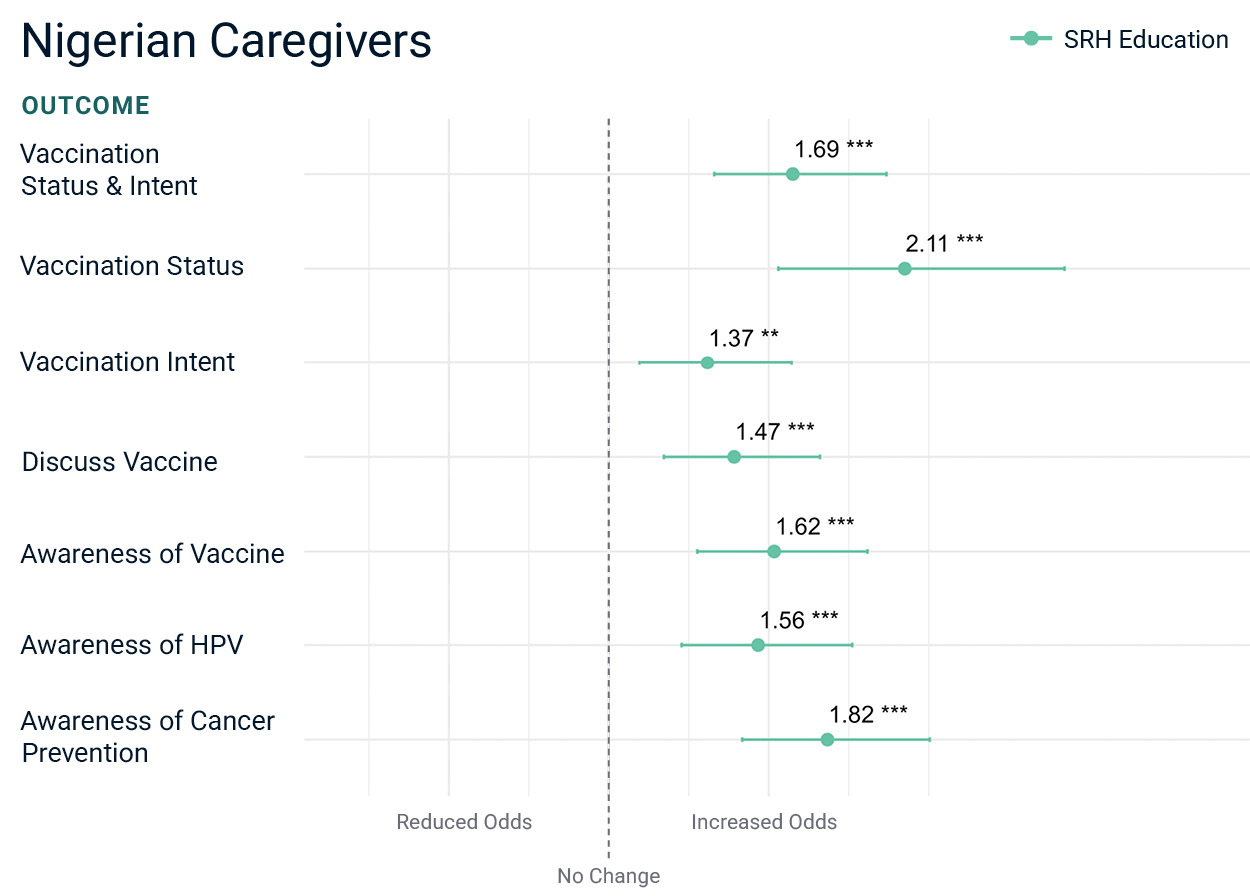

In Nigeria, perceived norms supportive of SRH education among both AGYW and caregivers are significantly associated with higher levels of HPV knowledge, intent to vaccinate, and actual vaccine uptake. These norms also predicted more frequent family and community discussions about the vaccine. For example, caregivers who endorsed these norms had more than twice the odds of vaccinating their daughters compared to those who did not, whereas among AGYW, endorsement of these norms was associated with a 52% increase in the odds of vaccination (Chart 1). By contrast, norms about AGYW’s access to stigma-free healthcare were not significantly associated with HPV-related outcomes for Nigerian AGYW.

AGYW

Caregivers

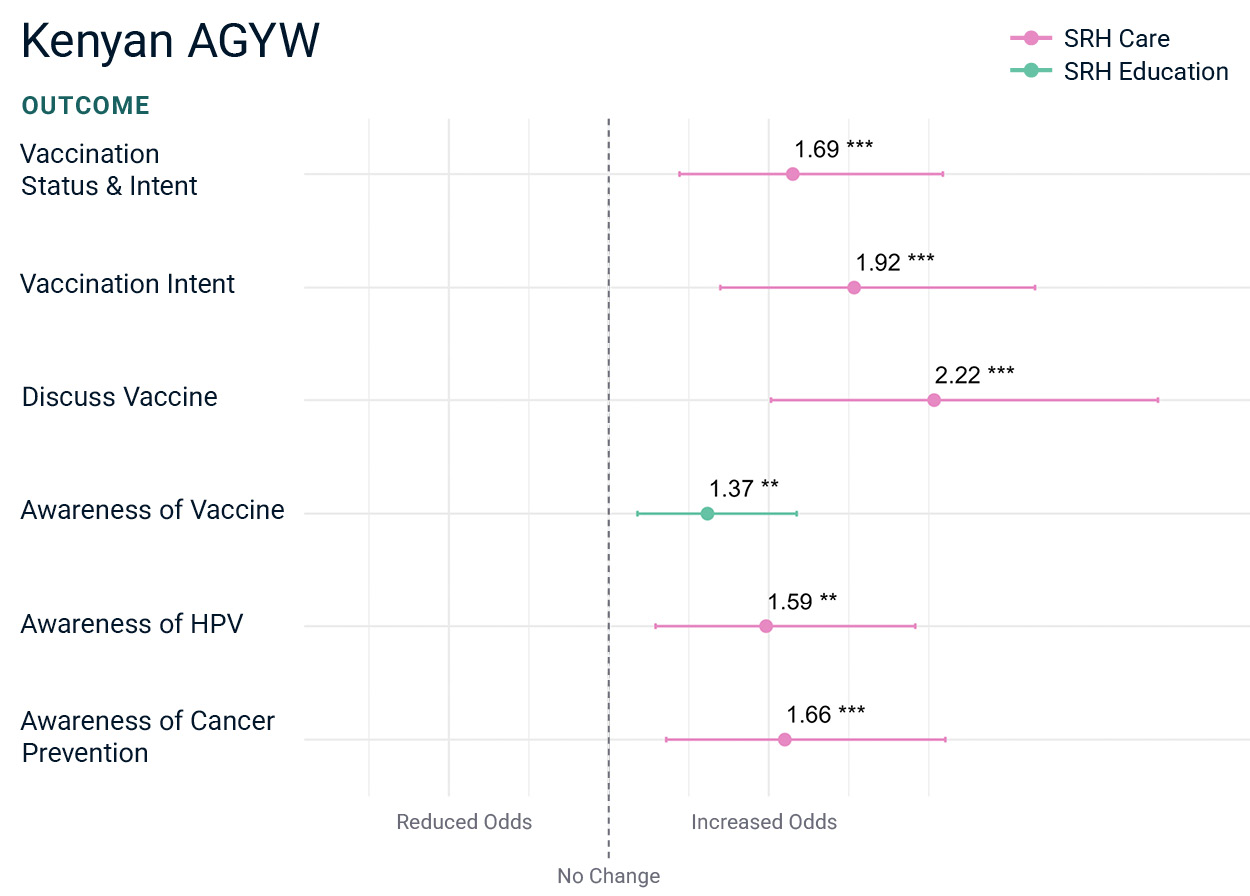

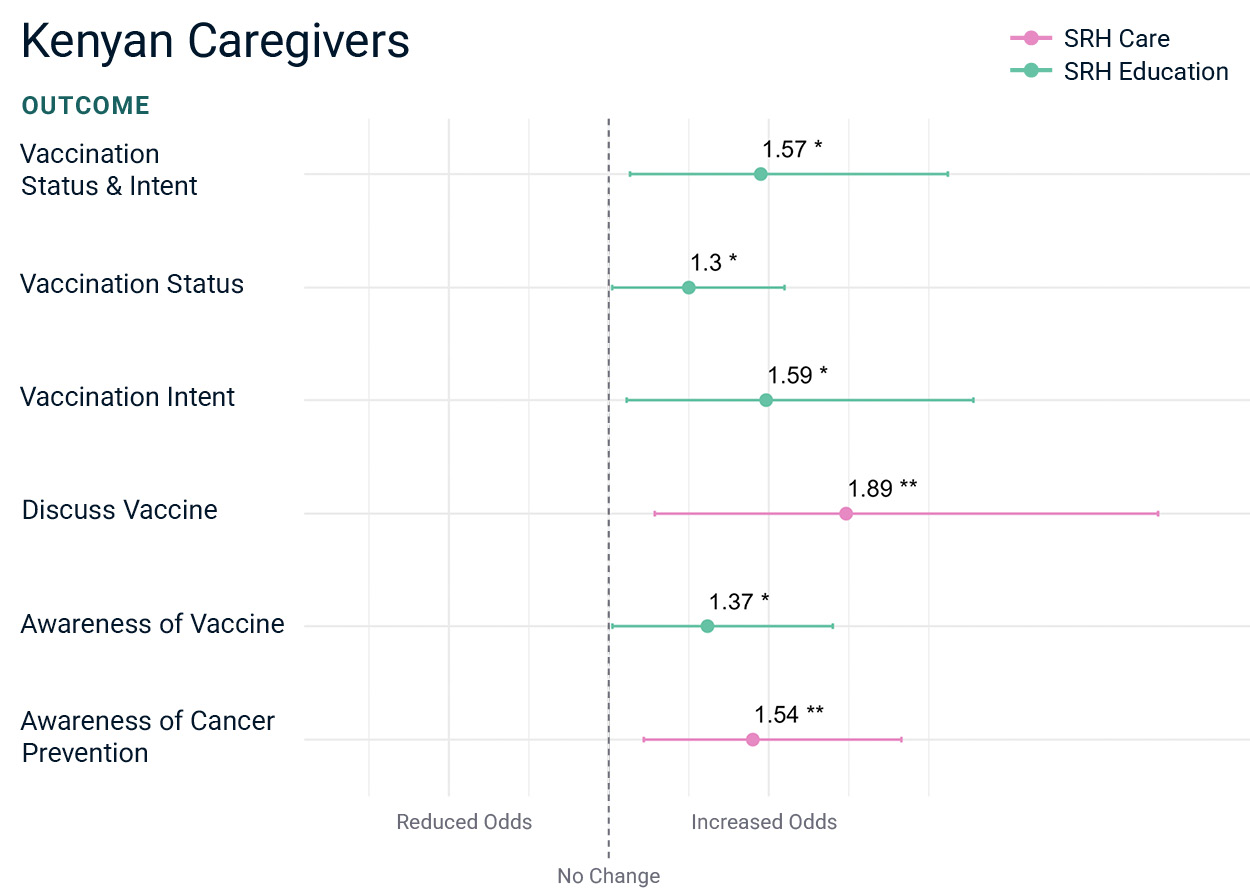

In Kenya, both SRH-related norms—support for education and access to care—were positively associated with HPV-related outcomes. Among caregivers, perceived support for girls’ SRH education was associated with a 30% increase in the odds of vaccinating their daughters and a 60% increase in the odds of intending to vaccinate, compared to those who did not perceive such support. For AGYW, norms supportive of access to health care without stigma were strongly associated with nearly twice the odds of intending to vaccinate and more than twice the odds of having conversations about the vaccine (see Chart 2).

Taken together, these findings highlight the especially influential role of SRH education norms in both countries, and the added importance of access-to-care norms in Kenya, particularly for AGYW. These insights point to the value of targeting health-related gender norms, particularly around education, as part of efforts to improve HPV vaccine uptake and knowledge across settings.

AGYW

Caregivers

Key Finding 2: Gender-Equitable Communities Are Linked to Greater HPV Knowledge and Uptake—Especially in Nigeria

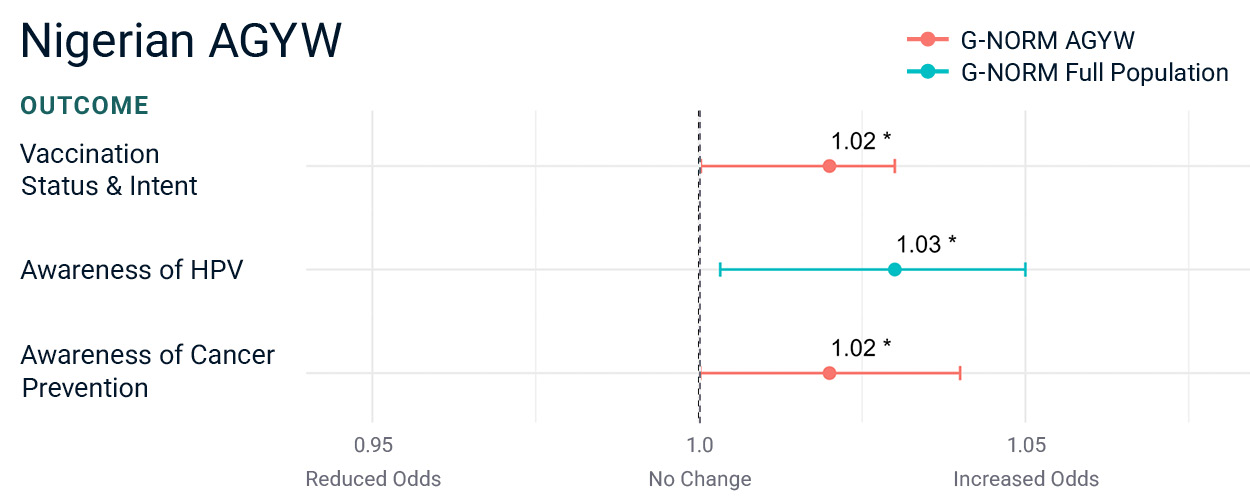

In Nigeria, AGYW living in communities with more gender-equitable norms—as measured by the G-NORM scale (which ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more gender-equitable views, especially when endorsed by peers)—had significantly higher odds of being vaccinated, intending to vaccinate, having greater knowledge about HPV, and understanding that the vaccine protects against cervical cancer, compared to AGYW in communities with less equitable norms (see Chart 3). No such relationship was observed in Kenya.

Although the odds ratios appear small (for example, 1.03 or 1.02), it’s important to remember that these figures reflect the effect of just a one-point increase on a 100-point scale. This means that even small increases in gender-equitable norms across a community can meaningfully shift HPV-related outcomes. For instance, a 10-point increase would correspond to roughly a 30% increase in the odds of a given outcome, which is substantial at a population level.

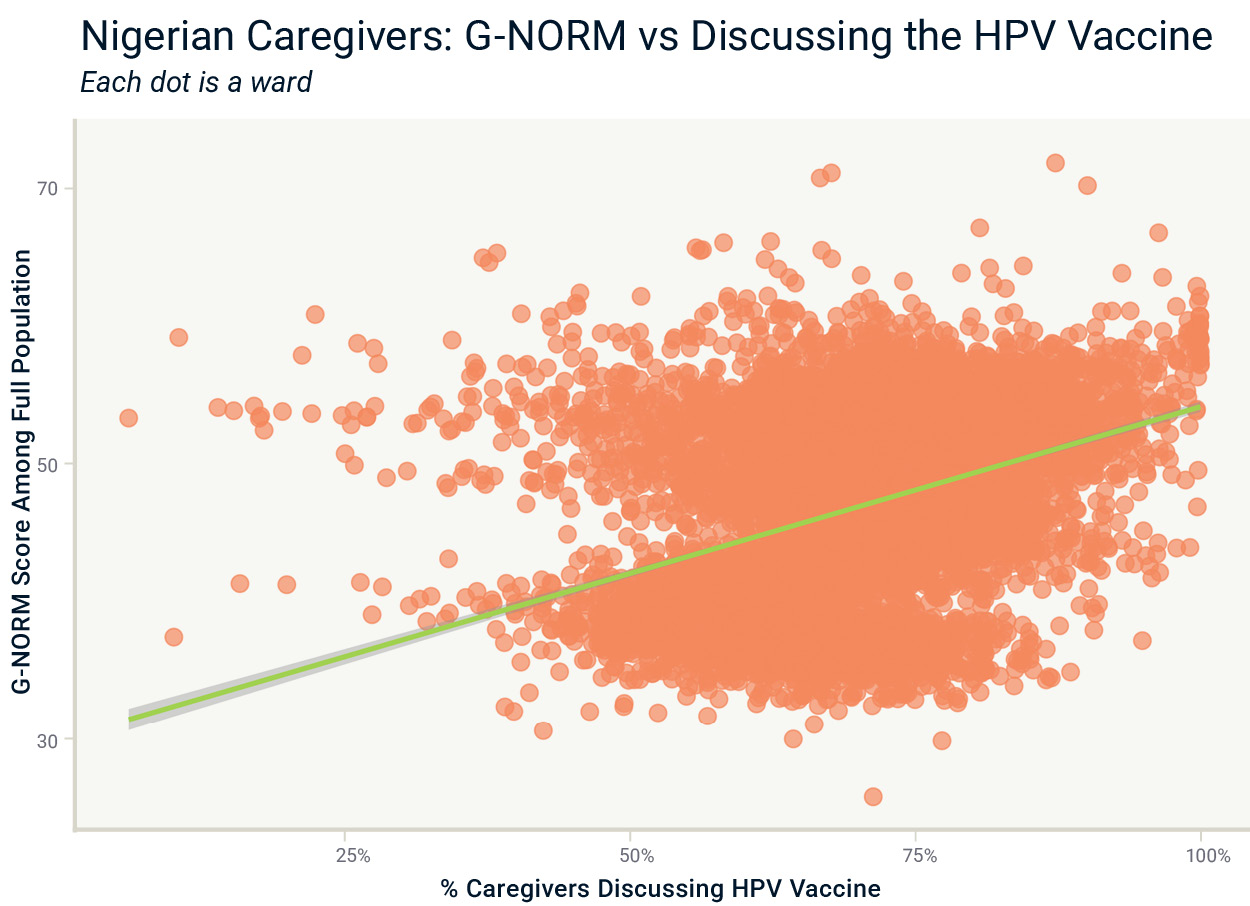

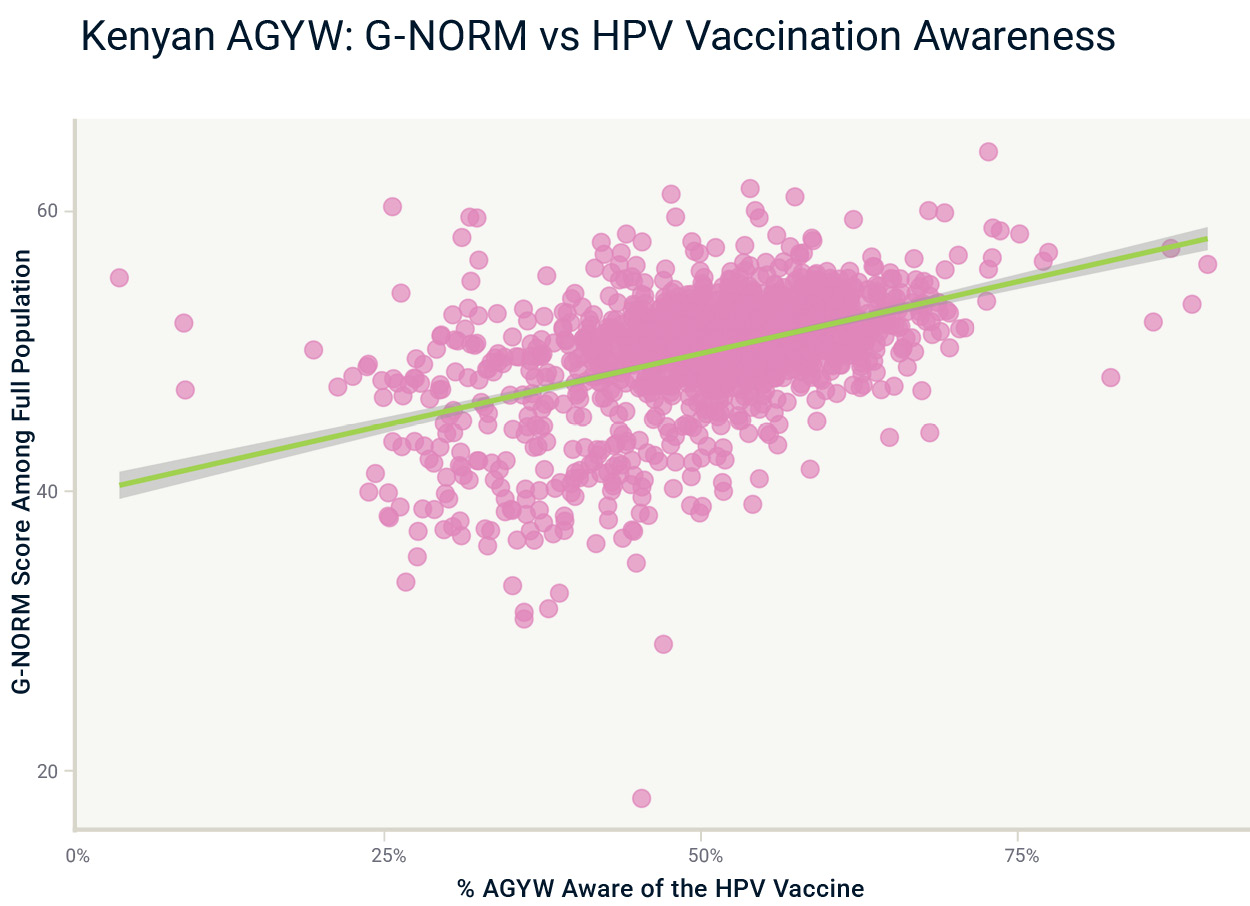

Community-level patterns in gender-equitable norms reinforce the link between supportive social environments and HPV-related behaviors. In both countries, though more modestly in Kenya (ρ = 0.23), wards with more gender-equitable norms had higher odds of caregivers reporting discussions about the HPV vaccine. These trends are visualized for Nigeria in Chart 4. In Kenya, gender-equitable communities also had higher levels of vaccine awareness, especially among AGYW (ρ = 0.46) as shown in Chart 5, and to a slightly lesser extent, among caregivers (ρ = 0.33).

Taken together, these findings suggest that gender-equitable norms at the community level shape not only individual behaviors but also collective ones, particularly around broader information-sharing dynamics. Communities subscribing to more gender-equitable norms are more likely to create enabling environments where SRH topics are openly discussed, and knowledge and acceptance of HPV vaccination are stronger.

Key Finding 3: Religious Leader Support Is A Strong Driver of HPV Vaccine Demand and Uptake In Both Countries

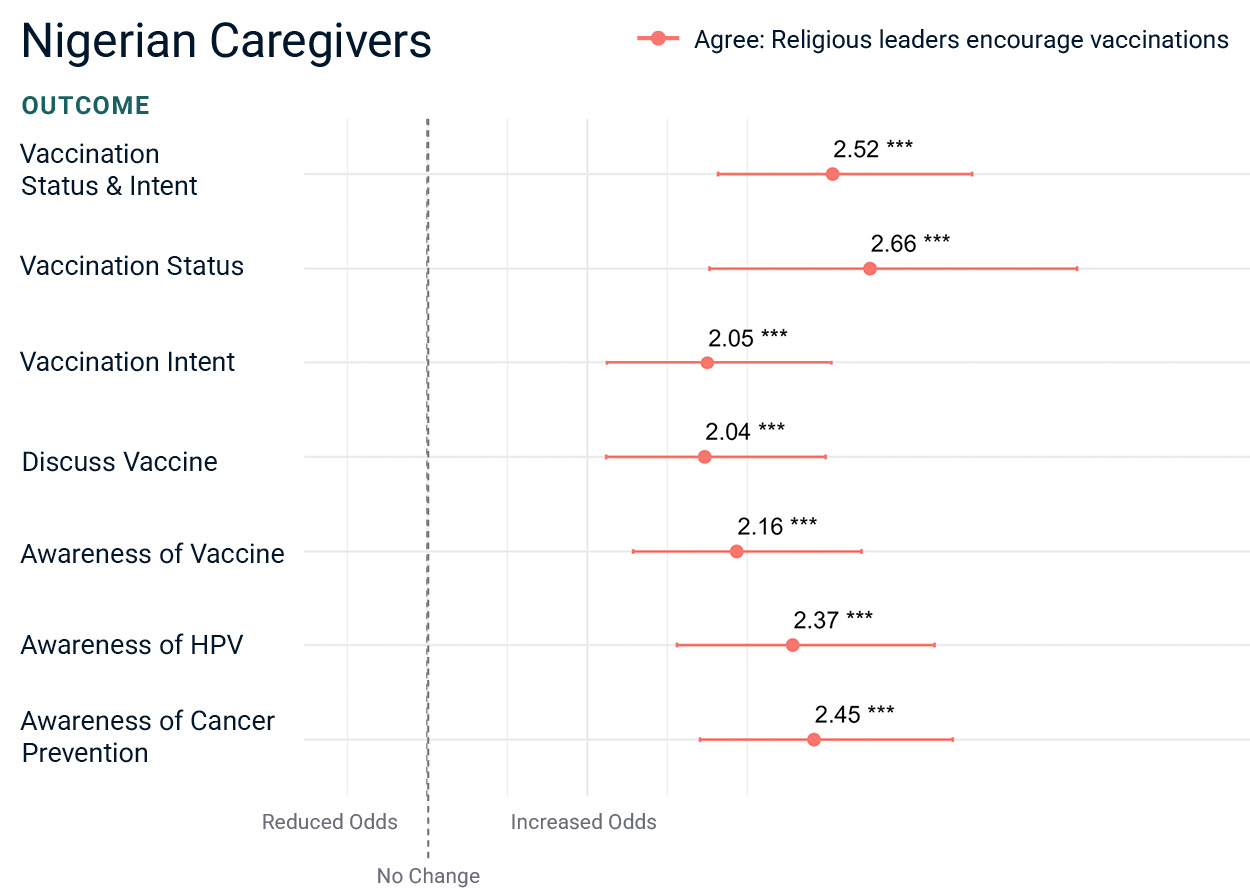

Fraym’s regression analysis shows that endorsements from religious leaders are strongly associated with improved HPV-related outcomes, particularly vaccination demand and uptake (Charts 6).

In Nigeria, caregivers who agreed that their religious leaders encouraged vaccination had nearly three times (OR = 2.76) higher odds of vaccinating their daughters than caregivers who did not, and the results are also similar (OR = 2.66) for AGYW. Nigerian caregivers perceiving religious support also have over twice the odds of intending to vaccinate their daughters (OR = 2.05) and discuss HPV vaccination (OR = 2.04). Furthermore, Nigerian caregivers perceiving religious support also had over two times higher odds of being aware of the virus (OR = 2.37), the vaccine (OR = 2.16), and HPV’s connection to cervical cancer (OR = 2.45) as compared to their counterparts who did not perceive support.

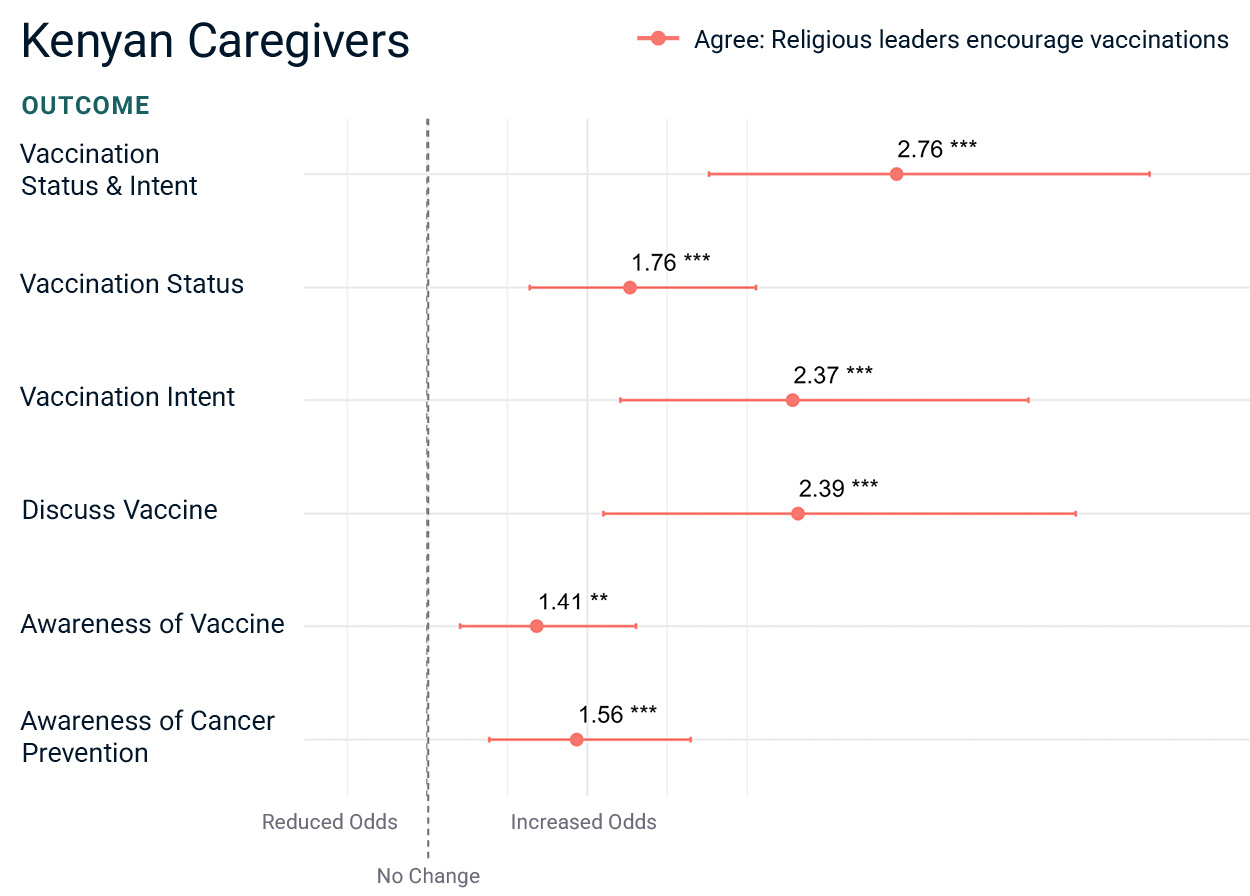

In Kenya, the pattern was consistent: both caregivers and AGYW who perceived religious leader support had significantly higher odds of reporting vaccine awareness, intention, and uptake. Kenyan caregivers who agreed about religious support had nearly two times higher odds (OR = 1.76) of having vaccinated their daughters than those who did not. Kenyan caregivers perceiving community religious support had over twice the odds of intending to vaccinate their daughters (OR = 2.37) or discussing the vaccine with friends or family (OR = 2.39) than those who did not. Kenyan AGYW perceiving community religious support had almost twice the odds of intending to vaccinate (OR = 1.93) or discussing the vaccine (OR = 1.92) than AGYW without such perceptions.

These findings underscore the influential role religious leaders can play in shaping vaccine-related behaviors and perceptions. Engaging faith actors may be a particularly effective strategy for increasing HPV vaccine acceptance and coverage across both countries.

Nigeria

Kenya

Key Finding 4: Geographic Diversity in Religious Influence Needs to be Considered for Targeted Programming

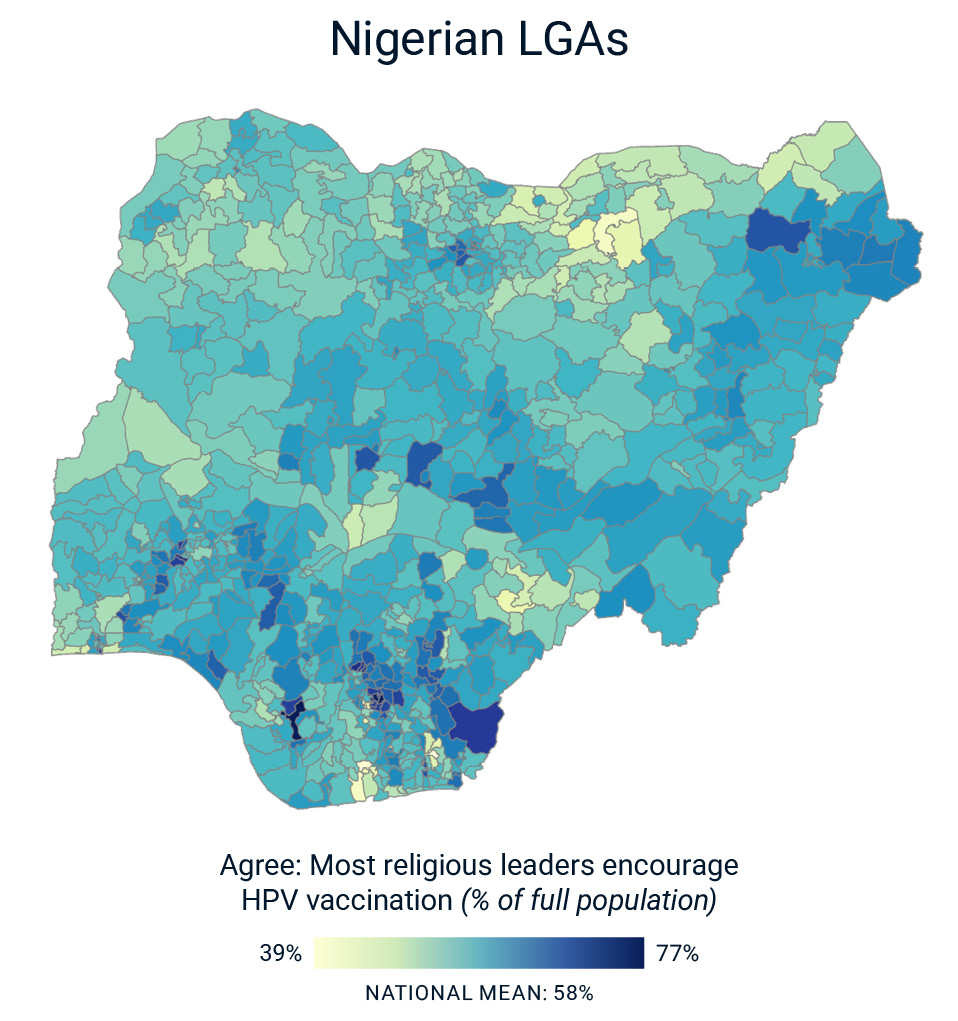

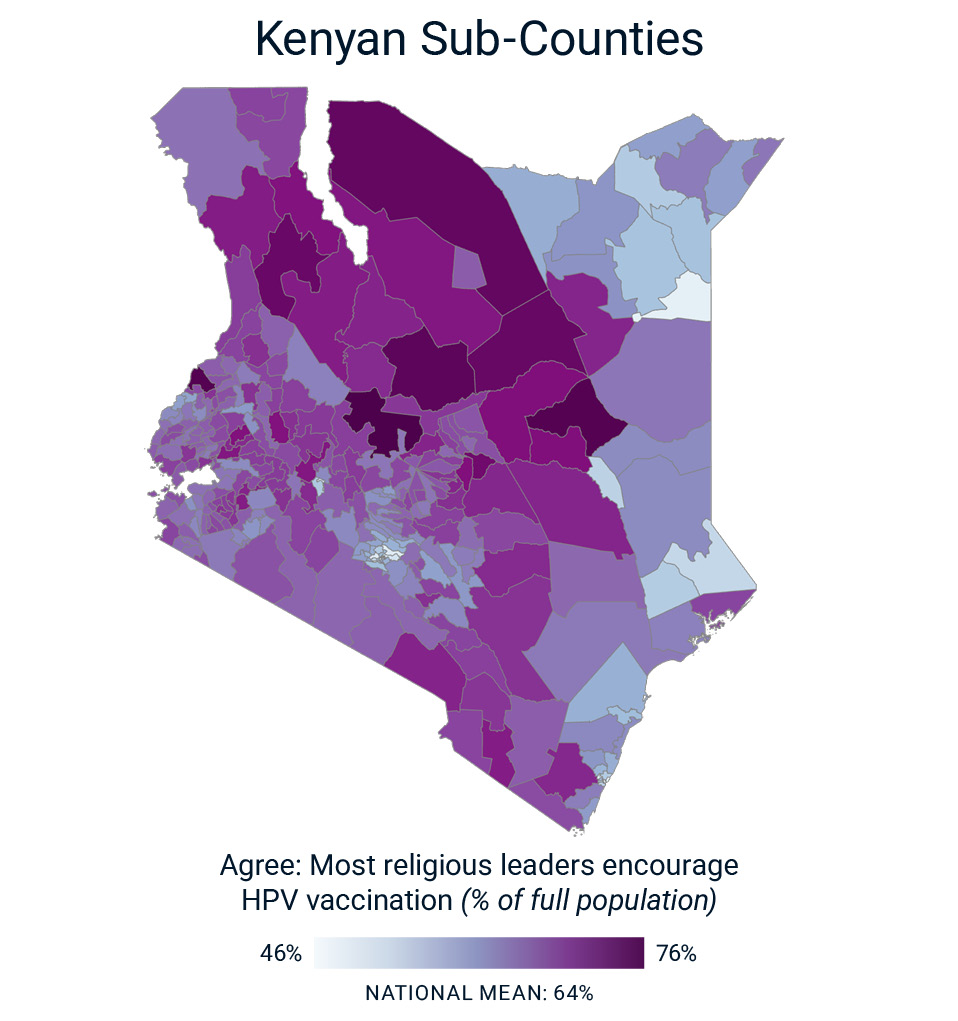

Although religious leaders’ support for the vaccine creates enabling environments for higher vaccination intention and uptake, Nigeria and Kenya each have large subnational geographic variation in religious support that may be relevant to locally targeted programming. Among Nigerian LGAs, there is wide variation in perceptions of religious support for HPV vaccination, with perceived religious support relatively higher in central and southern regions (Map 1). Likewise, among Kenyan sub-counties, perceptions of religious support for HPV vaccination also vary considerably, with stronger support in central and northern regions and lower support in coastal and northeastern areas. Subnational variation in baseline religious leaders’ encouragement of the vaccine may be relevant for designing targeted faith-based partnerships for HPV vaccination.

Map 1: Agree that Religious Leaders Encourage Vaccination

Map 2: Agree that Religious Leaders Encourage Vaccination

Implications and Recommendations

This research demonstrates how gender norms and religious endorsements shape HPV vaccine knowledge, demand, and uptake in Kenya and Nigeria. In Nigeria, communities with more gender-equitable norms foster higher awareness, intent, and vaccination among AGYW. In Kenya, the influence of gender norms was more nuanced but still evident, particularly around SRH education and stigma-free access to healthcare. Across both countries, norms that support AGYW’s access to SRH education consistently predicted better HPV-related outcomes. Religious leader support emerged as a particularly powerful factor, with endorsements associated with notably higher vaccine demand and uptake among both AGYW and caregivers.

These findings highlight a clear opportunity. By partnering with faith actors and promoting gender-equitable norms, stakeholders can foster enabling environments that support HPV vaccination and reduce cervical cancer risk. The following recommendations outline actionable strategies to leverage these insights.

With thoughtful, context-specific partnerships and sustained investments in norm change, HPV vaccination rates among AGYW can be significantly improved, bringing us closer to a future where no girl or young woman is left behind in the fight against cervical cancer.

Staats, A., John, N. (2025. Unlocking HPV Vaccine Uptake: The Role of Gender Norms and Faith in Kenya and Nigeria. The Gender Norms Data Engine. Arlington, VA: Fraym.

For questions or additional information, please contact:

Neetu John, PhD (Pronouns: she/her)

Principal, Gender Research & Programs

Email: [email protected]

Alabi, M. A., Bello, B. M., & Maina, B. W. (2024). Gender Norms and Attitude Towards Abortion Among Very Young Adolescents in Kenya and Nigeria (p. 2024.04.08.24305479). medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.08.24305479

Bormet, M., Kishoyian, J., Siame, Y., Ngalande, N., Erb, K., Parker, K., Huber, D., & Hardee, K. (2021). Faith-Based Advocacy for Family Planning Works: Evidence From Kenya and Zambia. Global Health: Science and Practice, 9(2), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00641

Dutta, T., Agley, J., Lin, H.-C., & Xiao, Y. (2021). Gender-responsive language in the National Policy Guidelines for Immunization in Kenya and changes in prevalence of tetanus vaccination among women, 2008–09 to 2014: A mixed methods study. Women’s Studies International Forum, 86, 102476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102476

ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. (2023). Kenya: Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers [Fact Sheet 2023]. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/KEN_FS.pdf

ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. (2023). Nigeria: Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers [Fact Sheet 2023]. Fact Sheet. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/NGA_FS.pdf

Jain, A., Ismail, H., Tobey, E., & Erulkar, A. (2019). Stigma as a barrier to family planning use among married youth in Ethiopia. Journal of Biosocial Science, 51(4), 505-519. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932018000305

Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative—Johns Hopkins CCP. (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://ccp.jhu.edu/projects/nigerian-urban-reproductive-health-initiative/

Riddle, A. UNICEF. (2024). Gender & Immunization Case Studies: Integrating Gender Considerations Into Nigeria’s Immunization Strategy: Lessons From The Full Portfolio Planning (Fpp) Process. https://www.unicef.org/media/166256/file/en-case-study-integrating-gender-immunization-strategy-Nigeria-2024.pdf.pdf

Sedlander, E., Granovsky, R., Birabwa, C., Amongin, D., Wasswa, R., Diamond-Smith, N., Waiswa, P., Holt, K., & Bingenheimer, J. B. (2024). Adaptation of the G-NORM (Gender norms scale) in Uganda: An examination of how gender norms are associated with reproductive health decision-making. PLOS ONE, 19(11), e0308249. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308249

World Health Organization. (2023). Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Coverage. [Dataset-Dashboard]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-vaccination-coverage