Unlocking HPV Vaccine Uptake

Blog

Despite free, school-based HPV vaccination programs in Kenya and Nigeria, most girls still aren’t fully protected against cervical cancer. Only 17% in Kenya and 27% in Nigeria receive the vaccine by age 15. Our research explores why: misinformation on social media, hesitancy shaped by community norms, and logistical challenges like unclear directions or distant clinics continue to prevent many families from taking action.

Using the WHO’s BeSD framework and nationally representative survey data, we show that what caregivers believe about vaccine safety—and what they hear from trusted sources—can be just as important as whether the vaccine is available. Even when caregivers intend to vaccinate, practical barriers often stop them from following through. This gap between intention and action contributes to persistently low coverage.

To close this gap, national programs must pair trusted, locally tailored education campaigns with high-quality, convenient service delivery. Granular, subnational data—such as local government area (LGA) level insights—can help target these efforts where they are needed most, ensuring programs address the right barriers in the right communities. When social and behavior change strategies are aligned with responsive delivery systems and data-driven targeting, Kenya and Nigeria can protect more girls and accelerate progress toward eliminating cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death among women in both Kenya and Nigeria (ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer, 2023). The vast majority of cases are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), a preventable infection for which safe, effective vaccines have been rolled out in free, school-based programs in both countries (ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer, 2023). Despite this, coverage remains alarmingly low; only 17% of eligible girls in Kenya and 27% in Nigeria are fully vaccinated by age 15 (World Health Organization, 2023).

These low rates persist even in well-resourced communities. In Lagos, for example, social media misinformation suppressed vaccine uptake until a nationwide awareness campaign was introduced (Ibeh, 2024). In Kenya, proactive sensitization still encountered resistance from faith-based actors, such as Catholic leadership (Karanja-Chege, 2022). These patterns suggest that logistical rollout alone isn’t enough to generate vaccine demand.

Nevertheless, access barriers like cost and distance can prevent even motivated caregivers from vaccinating their daughters against HPV, as evidenced by several pilot programs in both Kenya and Nigeria. In Kosofe LGA in Lagos, Nigeria, for instance, a school-based vaccination pilot improved vaccination coverage by eliminating caregiver requirements to travel or take time off work to vaccinate their children (Odis, 2023). In Kitui County in Kenya, a school-based pilot program furthermore achieved 96% coverage for HPV vaccination (Karanja-Chege, 2022). As such, cost and convenience are also relevant considerations for HPV vaccination programming.

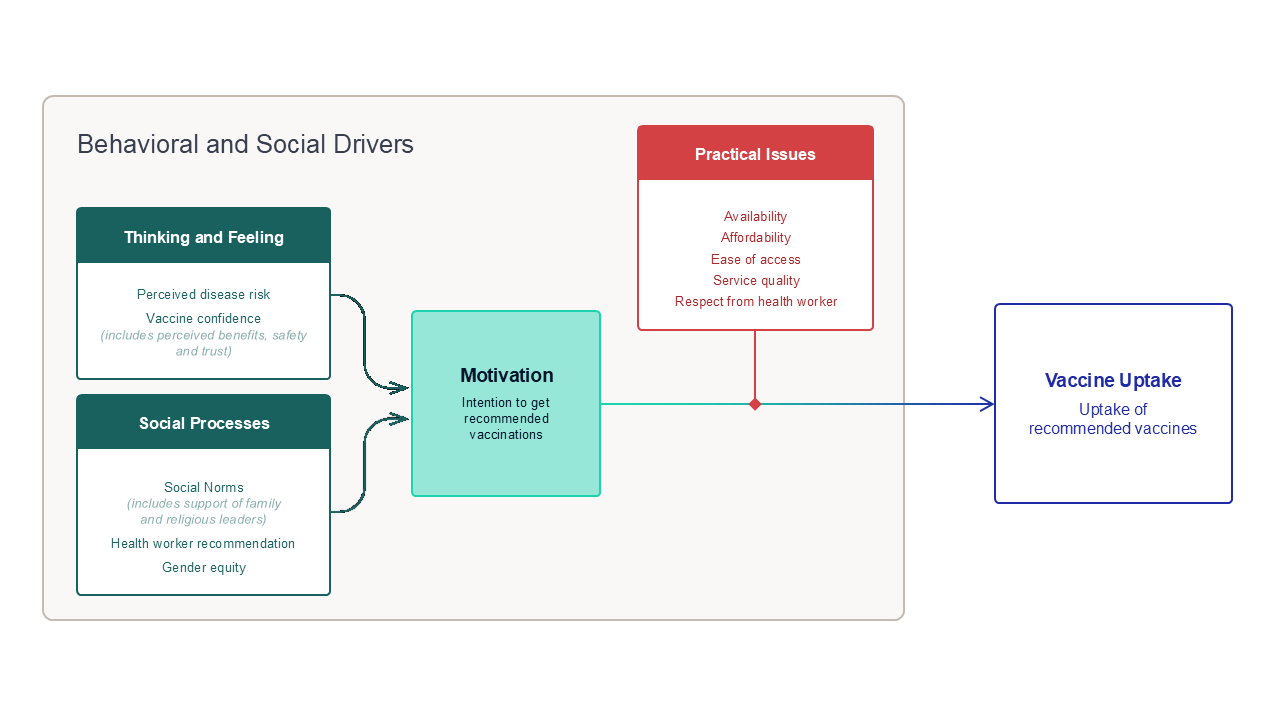

To better understand what drives HPV vaccine uptake, this brief applies the World Health Organization’s Behavioral and Social Drivers (BeSD) framework. According to BeSD, individuals’ beliefs and social environments—captured under the domains of “thinking and feeling” (e.g., vaccine confidence, perceived risk) and “social processes” (e.g., community norms, health worker recommendations)—shape their motivation or intention to vaccinate. However, intention alone does not ensure follow-through. Whether that motivation leads to actual vaccine uptake depends on practical factors like knowing where to go, ease of access, and satisfaction with services. This distinction helps explain the gap between motivation and action (World Health Organization, 2022).

This analysis builds on Fraym’s earlier research using the same dataset, which examined how gender norms and religious endorsements shaped HPV vaccine uptake among older adolescents (ages 15–24) and caregivers of girls aged 8–17 (Staats & John, 2025). In this brief, we focus specifically on caregivers, who are the primary decision-makers for girls aged 9–14—the main target population of national HPV vaccination programs. Using the BeSD framework, we explore how broader behavioral and social factors influence both caregivers’ intention to vaccinate and their daughters’ actual uptake of the HPV vaccine.

To explore these behavioral and social drivers, Fraym conducted nationally representative surveys in 2024 with caregivers of girls aged 8–17 in both Kenya (n = 2,089) and Nigeria (n = 3,903), as part of larger data collection efforts. While Fraym typically leverages spatial modeling to generate high-resolution estimates, this analysis focuses on individual-level survey data in order to examine relational drivers of behavior. Caregivers were asked about both intention to vaccinate (if their daughter was unvaccinated) and vaccination status (for all respondents), using adapted items from the WHO BeSD questionnaire (World Health Organization, 2022).

Within the BeSD “Thinking & Feeling” domain, we assessed caregivers’ perceptions of vaccine safety, efficacy, perceived risk of HPV infection (if their daughters remained unvaccinated), and the importance of the vaccine for overall health. To capture “Social Processes”, we included two items: whether caregivers believe most parents in their community support HPV vaccination, and whether a health care provider had recommended the vaccine for their daughter. Gender equity was explored in depth in our earlier blog. Due to space constraints, we excluded questions on affordability and perceived respect from health workers in this round.

Guided by the BeSD framework, we explored two key questions:

1. How do psychological (“thinking and feeling”) and normative (“social processes”) factors—such as perceived risk or belief in community support—influence intention to vaccinate?

2. How do practical issues—such as satisfaction with services or knowing where to go—affect actual vaccine uptake?

We used multivariate logistic regression models to estimate the predictive effect of each driver, adjusting for caregiver age, region, urbanicity, religion, education, and household wealth. To aid interpretation, we translated odds ratios into adjusted predicted probabilities under two conditions—assuming the presence versus absence of a given belief or barrier—allowing us to express each driver’s impact in real-world percentage terms.

Key Finding 1: Beliefs About Vaccine Safety and Community Support Powerfully Shape Caregivers’ Intent to Vaccinate Their Daughters.

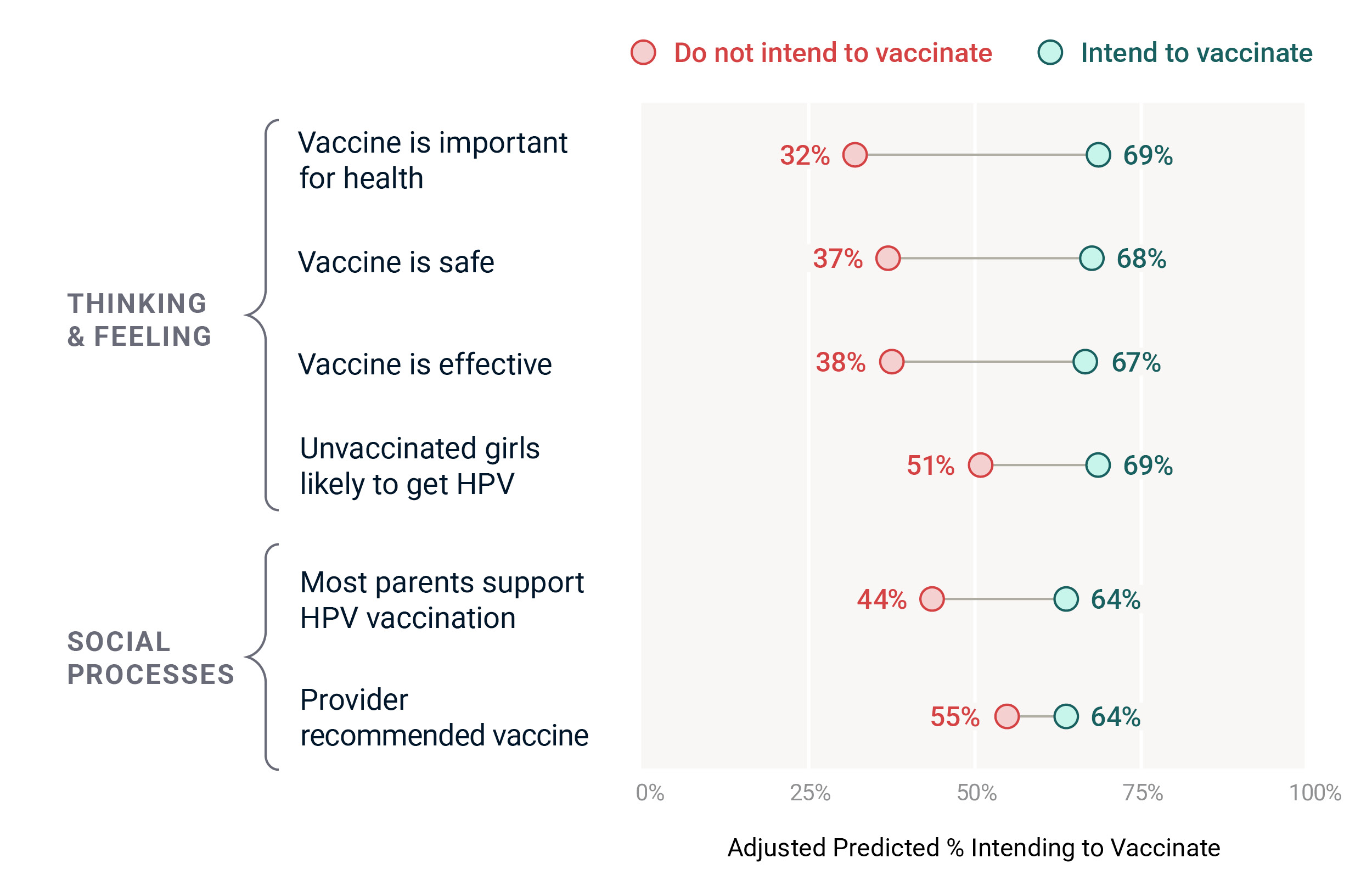

Caregivers’ beliefs about the HPV vaccine—especially whether they think it is safe, effective, and important for girls’ health—strongly influence their intention to vaccinate. These “thinking and feeling” factors, along with social cues like community norms and provider recommendations, emerge as important behavioral drivers across both Kenya and Nigeria.

In Nigeria, for example, caregivers who believe the vaccine is safe are 31 percentage points more likely to intend to vaccinate their daughters compared to those who do not share that belief (68% vs. 37%). Similarly, believing the vaccine is effective or important for health also raises predicted intention levels substantially.

Social processes matter as well. Caregivers who believe that most other parents support HPV vaccination are 20 points more likely to intend to vaccinate (64% vs. 44%). Those who report receiving a recommendation from a health worker also show meaningfully higher predicted intent.

These effects are presented in Chart 2, which shows adjusted predicted probabilities from separate multivariate models. Each line compares the likelihood of intending to vaccinate between caregivers who do and do not hold a specific belief or receive a recommendation, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

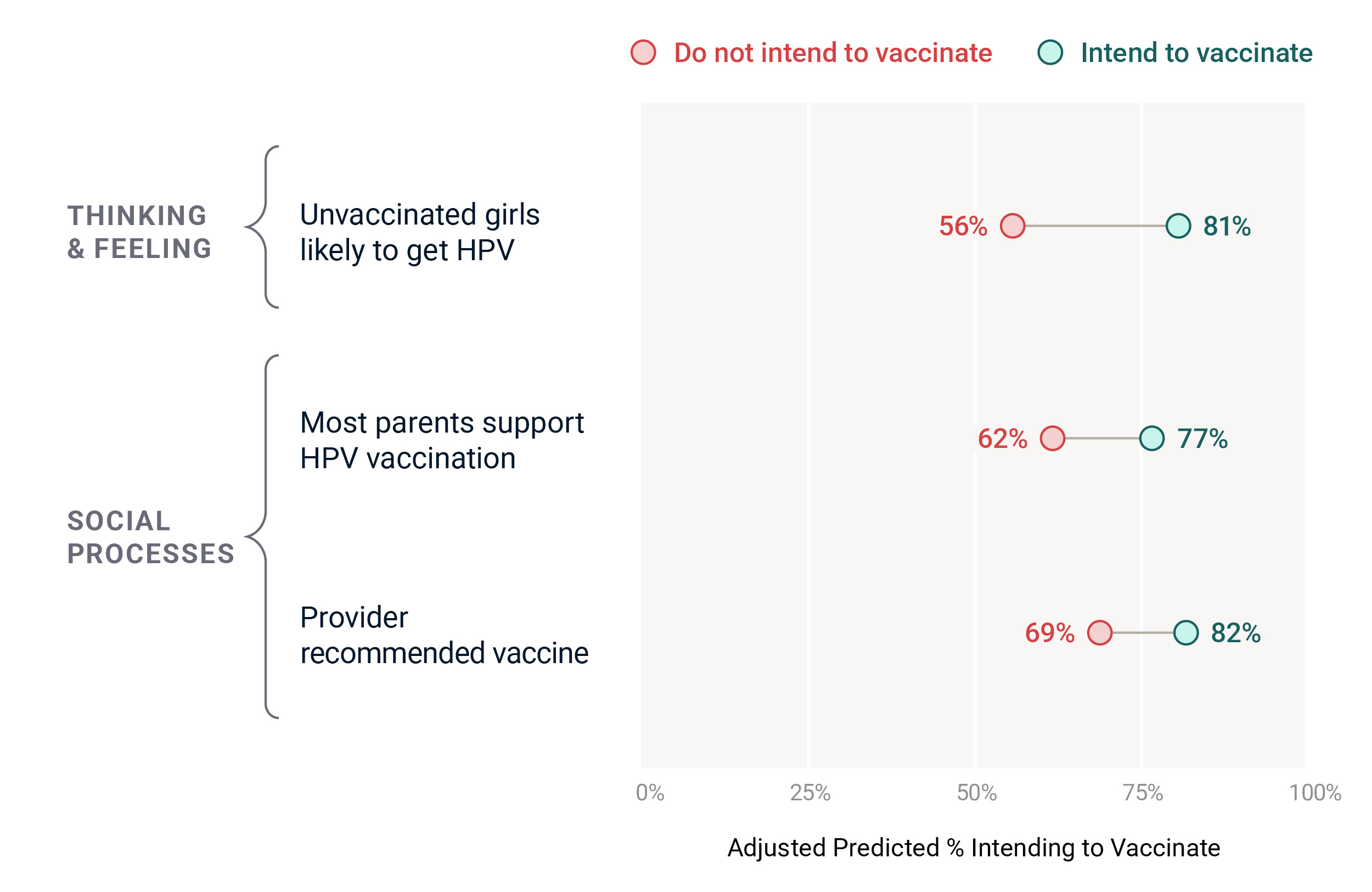

In Kenya, the belief that unvaccinated girls are likely to get HPV is the strongest predictor of caregiver intention to vaccinate. Caregivers who hold this belief are 25 percentage points more likely to plan to vaccinate their daughters than those who do not (81% vs. 56%). Social support factors also play a meaningful role. A health worker recommendation is linked to a 13-point increase in intention (82% vs. 69%), and believing that most other parents support HPV vaccination is associated with a 15-point difference (77% vs. 62%) (Chart 3).

* Adjusted predicted probabilities from multivariate logistic regression models

Together, these findings suggest that what caregivers believe about the HPV vaccine and what they hear from trusted people both shape their decisions. Programs that strengthen confidence in the vaccine and make visible the support of health workers and peers can help increase demand for HPV vaccination. Because social and behavior change communication (SBCC) approaches can be both scalable and cost-effective, investing in well-designed messaging strategies offers a high-impact way to improve HPV vaccine uptake.

Key Finding 2: Access Challenges Like Location, Convenience, and Service Experience Limit Vaccine Uptake.

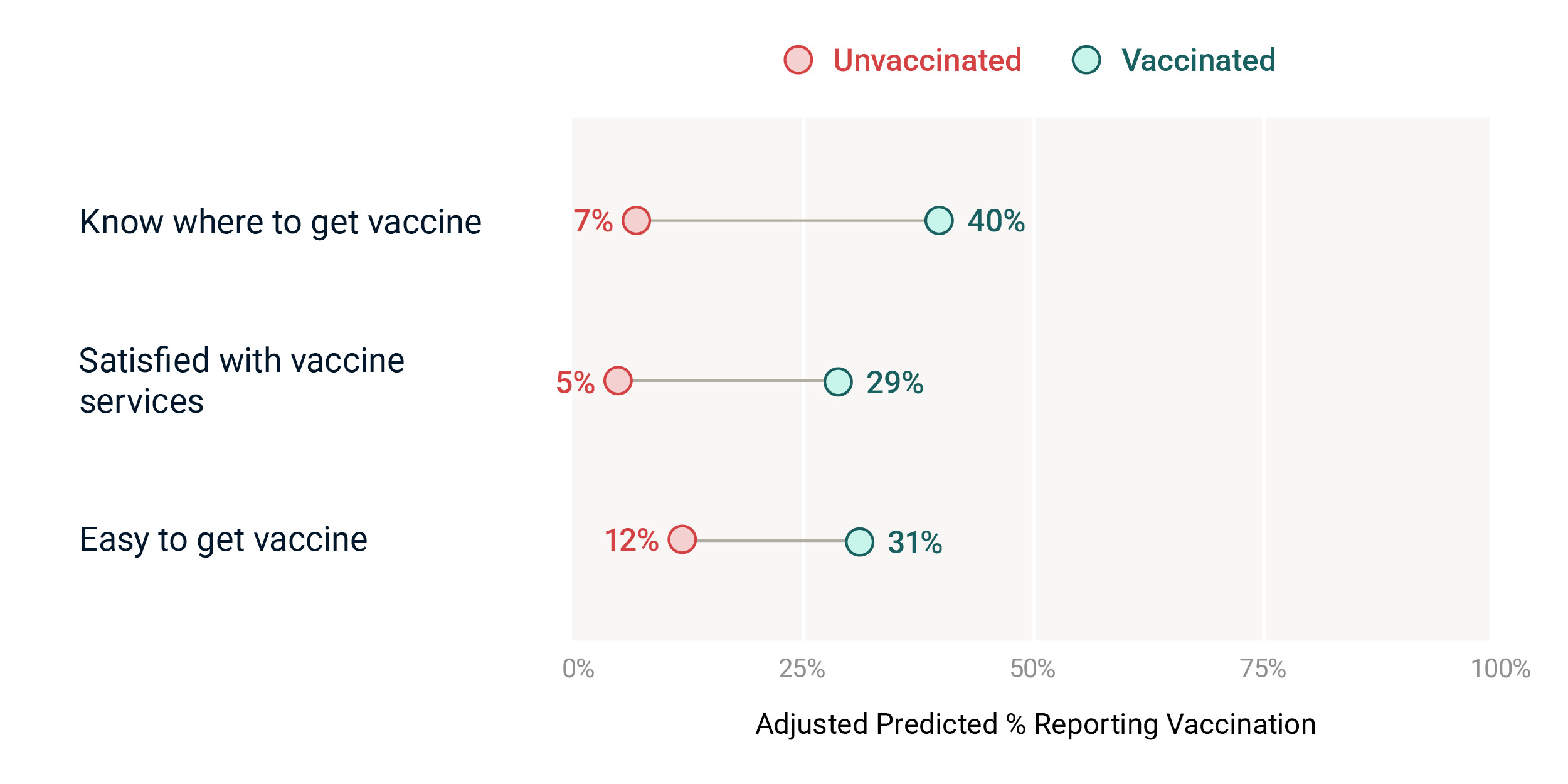

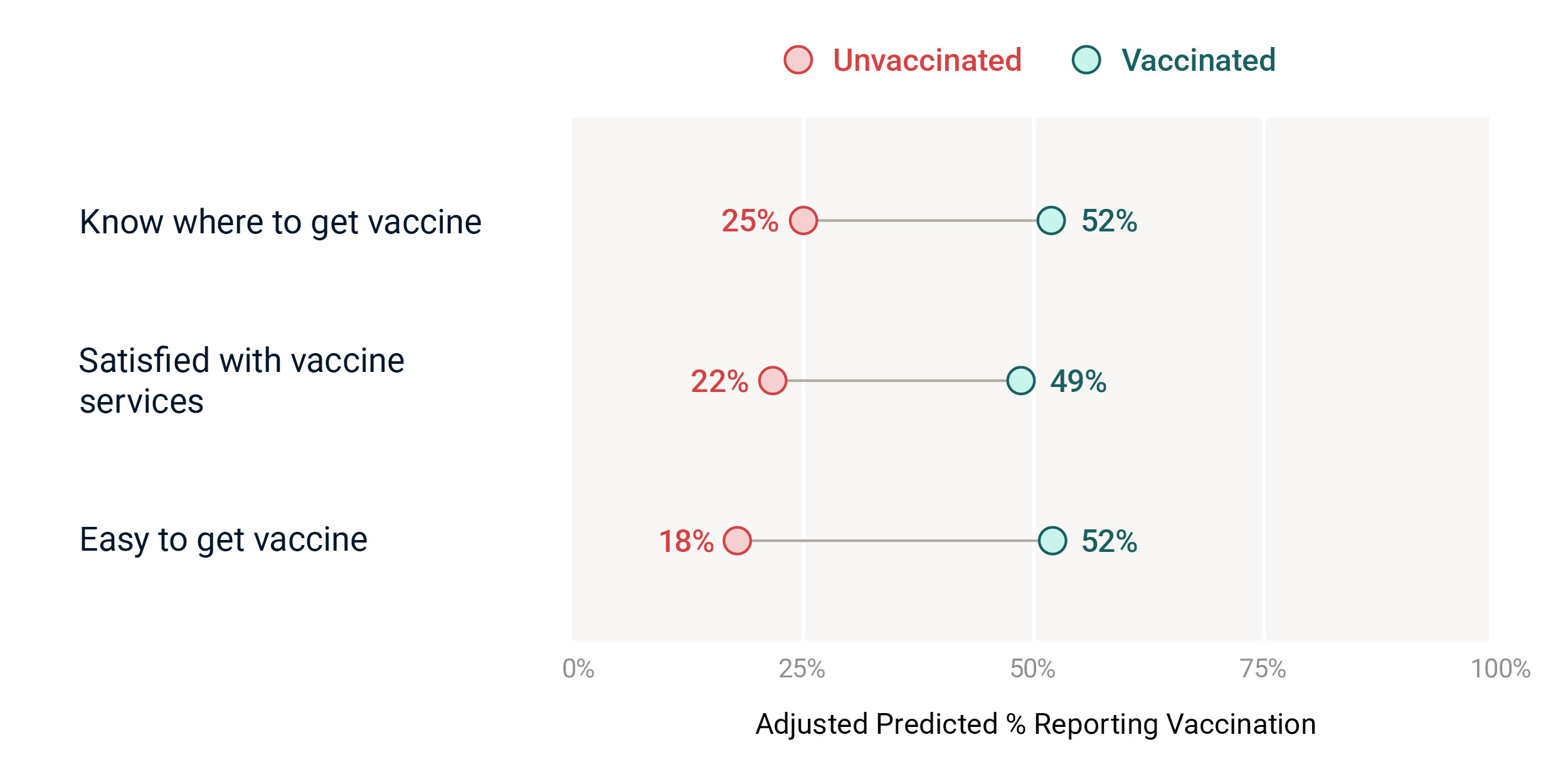

Across both Nigeria and Kenya, caregivers were far more likely to have vaccinated their daughters when they had basic logistical support. Knowing where to go, finding services easy to access, and feeling satisfied with the vaccination experience all made a measurable difference in uptake. These practical issues often determine whether motivated caregivers are able to follow through with getting their daughters vaccinated.

In Nigeria, these access-related factors have a particularly strong influence. Caregivers who know where to go for the vaccine were 37 percentage points more likely to report that their daughters are vaccinated, compared to those who didn’t (44% vs. 7%). Satisfaction with the vaccination experience also mattered. Those satisfied with services are 24 points more likely to report uptake (29% vs. 5%). And ease of access mattered too, with a 19-point difference between caregivers who said getting the vaccine was easy versus those who didn’t (31% vs. 12%). These differences are shown in Chart 4, which presents adjusted predicted probabilities of vaccination status based on separate regression models for each access factor.

* Adjusted predicted probabilities from multivariate logistic regression models.

In Kenya, the picture is similar. Caregivers who have clear information about where to go or feel satisfied with services are 27 percentage points more likely to have vaccinated their daughters. Those who said vaccination was easy to access had a 24-point increase in uptake (Chart 5). These findings reinforce that when services are harder to find or less convenient, uptake suffers—even when the vaccine is free.

* Adjusted predicted probabilities from multivariate logistic regression models.

Taken together, these findings show that cost is not the only barrier. Even when vaccines are free, many girls still miss out if caregivers face practical challenges like unclear information, inconvenient service locations, or poor service experience. Addressing these issues is critical. Improving access through school-based delivery, mobile outreach, or better service quality can help ensure that more caregivers can act on their intention to vaccinate, especially in communities that are lower-income or harder to reach.

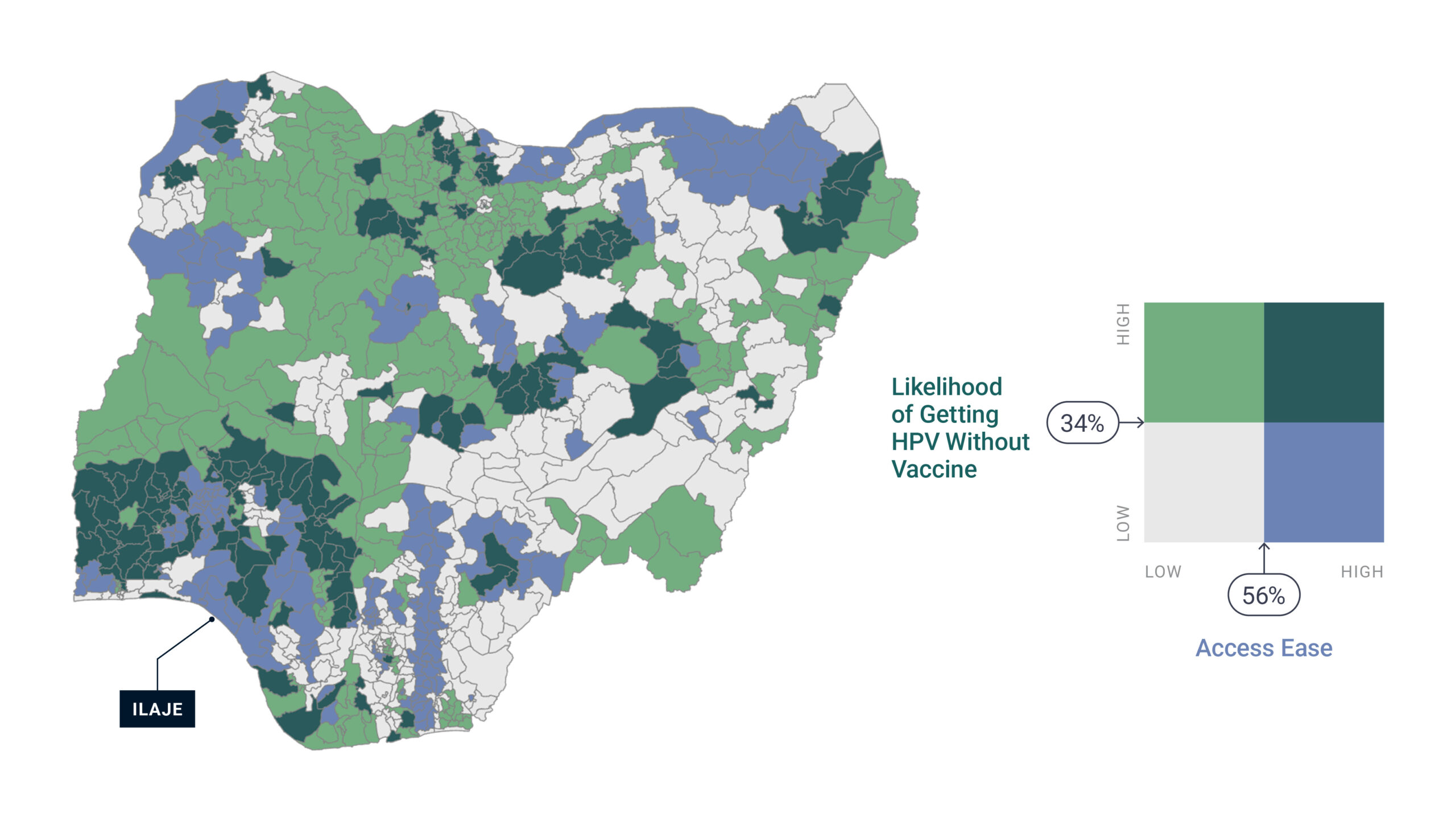

Key Finding 3: Motivation and Access Gaps Vary Widely Across Communities

Not all communities face the same barriers to HPV vaccination. In some areas, caregivers are motivated to vaccinate—because they believe in the vaccine’s benefits or perceive HPV as a real threat—but they struggle with practical challenges such as knowing where to go or finding services that are convenient and welcoming. In other communities, services may be available and easy to reach, but caregivers are less likely to vaccinate because they are uncertain about the vaccine’s safety or do not believe HPV poses a serious risk. This variation highlights why national averages can obscure important subnational differences—and why localized, adaptive programming is essential.

To explore this variation, we used data from Nigeria to compare two key drivers drawn from the BeSD framework: caregivers’ perceived risk of HPV, which reflects their motivation to vaccinate, and their reported ease of accessing vaccination services, which reflects whether that motivation is likely to translate into actual uptake. These two factors were combined in a bivariate map (Map 1) to show how barrier types differ across LGAs.

LGAs shaded dark green reflect areas where both motivation and access are high, suggesting that caregivers are both willing and able to vaccinate. These communities are well-positioned for strong uptake and may only need continued reinforcement. In contrast, grey-shaded LGAs show low levels of both motivation and access, indicating a need for integrated approaches that simultaneously build awareness and reduce logistical challenges. In some LGAs, such as those shaded light green, motivation is relatively high but access is limited, pointing to practical access barriers as the primary bottleneck. Conversely, light blue areas show the opposite pattern—caregivers perceive HPV as low risk but report that services are easy to access—highlighting psychological or informational barriers as the dominant issue.

For example, in Ilaje, a LGA in Ondo State, 80% of caregivers report that HPV services are easy to access, yet only 21% believe that unvaccinated girls are likely to contract HPV. This mismatch suggests that, in Ilaje, improving service delivery alone will not be enough; public health programming should also focus on building confidence in the vaccine and communicating the risks of HPV more clearly and consistently.

This kind of subnational analysis allows service providers and implementing partners to go beyond identifying whether barriers exist to understanding what kind of barriers exist, and where. These insights are critical for targeting the right intervention to the right place. In some communities, strengthening demand through social and behavior change communication will be key. In others, increasing convenience and service quality will help caregivers act on their intentions. And, in many cases, both will be needed. While the HPV vaccine is now free in both Kenya and Nigeria, this analysis underscores that free is not the same as accessible—and that bridging the gap between motivation and uptake requires locally tailored solutions.

IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This research illustrates how psychological, social, and practical factors, captured in the WHO’s BeSD framework, influence HPV vaccination intention and uptake in Kenya and Nigeria. Across both countries, beliefs about vaccine safety, efficacy, and benefits were strong predictors of caregivers’ intention to vaccinate. At the same time, practical considerations, such as knowing where to go and satisfaction with services, meaningfully shaped whether daughters have been vaccinated. These findings confirm that the BeSD framework, while originally developed for childhood vaccination, is highly relevant to HPV vaccine delivery. They also show that different types of barriers matter at different stages of the vaccination pathway (Chart 1).

Together, these insights point to the need for a multi-pronged approach to HPV vaccination that includes both education and service delivery components and is tailored to local geographies. Recent experience from Lagos highlights this clearly: online anti-vaccine campaigns suppressed vaccine demand during the early rollout, delaying uptake despite available services (Ibeh, 2024). At the same time, even when vaccines are free, caregivers may still face practical challenges, including transportation, missed work, or unclear delivery information. In-school delivery helps reduce these costs but may still exclude vulnerable, out-of-school girls.

Based on these findings, successful national HPV vaccination programs should prioritize three interlinked strategies, adjusting intensity and focus based on community context:

The path to a future free from cervical cancer runs through communities. Both demand and delivery must meet people where they are. A strategy that combines behaviorally informed messaging with high-quality, locally tailored service delivery will be essential to close the gap between vaccine intention and uptake.

This approach not only supports national priorities but also directly advances the World Health Organization’s global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer, which calls for 90 percent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV by age 15, 70 percent to be screened for cervical disease, and 90 percent of those diagnosed to receive treatment. Reaching these goals in Kenya and Nigeria will require not just stronger programs, but smarter, more data-driven ones.

Staats, A., & John, N. (2025). Beyond availability: What drives HPV vaccine uptake in Kenya and Nigeria? The Data Engine. Arlington, VA: Fraym.

For questions or additional information, please contact:

Neetu John, PhD (Pronouns: she/her)

Principal, Gender Research & Programs

Email: [email protected]

Ibeh, Royal. (2024). Lagos aims to reach 1 million girls with cancer-blocking HPV shot by year’s end. Gavi. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/lagos-aims-reach-1m-girls-cancer-blocking-hpv-shot-years-end

ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. (2023). Kenya: Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers [Fact Sheet 2023]. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/KEN_FS.pdf

ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. (2023). Nigeria: Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers [Fact Sheet 2023]. Fact Sheet. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/NGA_FS.pdf

Karanja-Chege, C. M. (2022). HPV Vaccination in Kenya: The Challenges Faced and Strategies to Increase Uptake. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 802947. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.802947

Ochomo, E. O., Tonui, P., Muthoka, K., Amboka, S., Itsura, P., Omenge Orang’o, E., Rosen, B., Loehrer, P., & Cu-Uvin, S. (2024). Addressing HPV vaccine hesitancy: Unveiling concerns and building trust’ perspectives of adolescent girls and parents in Kisumu County, Kenya. Ecancermedicalscience, 18. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2024.1735

Odis, A. (2023). Integrating Health Services into Education: School-Based Vaccination in Lagos, Nigeria. Sabin Vaccine Institue. https://www.sabin.org/resources/integrating-health-services-into-education-school-based-vaccination-in-lagos-nigeria/

Staats, A., John, N. (2025). Unlocking HPV Vaccine Uptake: The Role of Gender Norms and Faith in Kenya and Nigeria. The Gender Norms Data Engine. Arlington, VA: Fraym. https://fraym.io/blog/unlocking-hpv-vaccine-uptake/

World Health Organization. (2022). Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/354459

World Health Organization. (2023). Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Coverage. [Dataset-Dashboard]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-vaccination-coverage